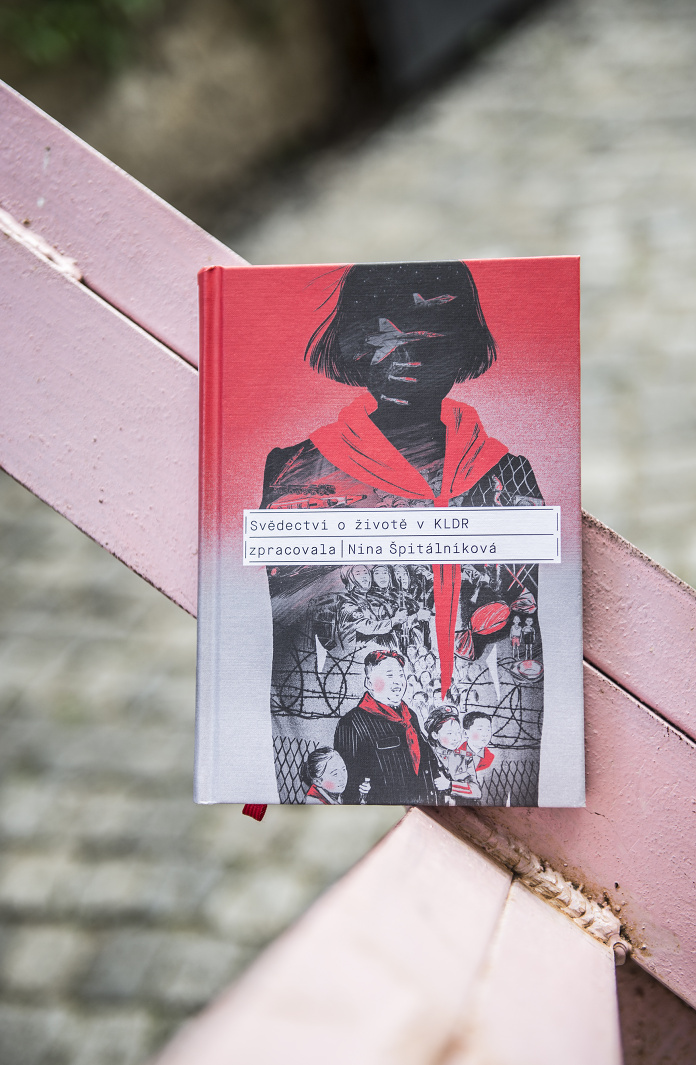

A specialist in North Korean studies, activist and feminist. That is how (not just the Czech media but also her home faculty) describe Nina Špitálníková, a student of Oral and Contemporary History at the Faculty of Humanities of Charles University. Her book Witnessing Life in the DPRK (2020) became a bestseller and won the Magnesia Litera Award in the category of journalism.

How did you become interested in life in North Korea?

I didn't go to college right after high school… and went through a somewhat “wilder” period but after a year or so I realised it wasn’t a good idea and applied for Japanese studies. I applied for Sinology as well, and on the advice of my then boyfriend, also applied for Korean Studies. In the end, that’s where I was accepted. I never regretted it. The teachers here were great and I enjoyed the lectures very much. During my studies that I developed a love for the Korean peninsula. I must admit, however, that I never thought I would make a living in this field. At that time, I was active in the cultural sphere and assumed that my main source of livelihood would be in this area...

You have yet to complete your Master's, is that right?

I failed the compulsory exam in another Asian language. Otherwise, all I had to do was finish my thesis. Now I am studying for my Master's degree at the Faculty of Humanities, where I am focusing on oral history and contemporary history.

Were you motivated to do this because of interviews you had conducted with North Koreans?

There were several reasons. I have always been more interested in history and literature than language. In addition, I realised that I had quite big gaps in the history of Europe and Czechoslovakia and I wanted to make up for it. It's true that by the time I applied to the Faculty of Humanities at CU, I had already been interviewing North Korean refugees for three years, and I realized that I was doing it kind of on a “punk” level. I felt I could use some professional insight. I have to say that I got hooked on the study because there's a great group of teachers here who support us. Ego has never played a role. Did your approach to interviewing change during your studies? Do you tell yourself that you should have - or could have - done something differently? Or better?

Did your approach to interviewing change during your studies? Do you tell yourself that you should have - or could have - done something differently? Or better?

The change came not so much in relation to studying history, but to having a child. The original interviews were tougher on the North Koreans and I was more interested in political topics. When I got pregnant, I became much more concerned with everyday life, which I found more interesting. The structure of the conversation suddenly changed spontaneously. None of the first ones are even in the book.

How did you choose the interviews to be published?

Actually, that was probably the most difficult part of the whole work, because I collected about eighty interviews in all. Some of them I eliminated outright, because in retrospect I admit that they were really bad. Others I had to throw out because I wasn't sure if the person was telling the truth. Sometimes I felt that the respondent was trying to come to terms with the past by rehashing it a lot.

When you met, you usually didn't know who was coming until the last minute, so you couldn't prepare for the interview in advance. How taxing was that on your psyche?

I was really nervous at first, and my age played a part in that. I did my first interviews when I was 27. At first I was expecting a big sensation: a North Korean would come and would reveal something mysterious, forbidden! But over time, my approach changed; now it's all about humanity. I have also developed a certain pattern of questions and I know how to verify and check the relevant information.

Were you able to avoid becoming emotionally involved in the stories? Not helping the interviewees?

I guess that's where I have the advantage of being completely emotionless during the interview. Could it be because I come from a police family background? Communication with my father often felt like an interrogation, so maybe that left an impact on me (laughs). Most of the time, everything hit me only back at the hotel, where I often broke down. The crying came afterwards; on the spot, I was able to filter out all of my emotions.

I'm quite realistic about helping. You can't help the North Koreans very much. The regime has such a tight grip that t any sending of humanitarian aid is unrealistic. There are organizations that help North Koreans escape. However, when you look at the annual and see what percentage costs in management and what percentage goes to actual aid, it’s discouraging.

Was the atmosphere ever so tense in an interview that is became impossible to finish?

That happened several times. I also soon found out that there was no point in doing interviews for more than an hour and a half, because reminiscing exhausts people. I have also accumulated several interviews that the interviewees decided not to publish at all, even for academic purposes. I fully respect that, of course. I gave everyone the opportunity to determine how they wanted to handle their story. For me, it was important to get the information for myself, and in fact, I did not expect the outcome to be a book at all... My goal was to understand why certain things happen.

So what was the impetus for the book?

I originally planned to write a novel. It was going to be the story of a young North Korean narrator, and it really struck me. I thought it would be safer to think of her life as fiction. The publisher accepted my idea and I started writing, but it took me six months to write just six pages. I realised that I probably wasn't creative enough, that I didn't have it in me to write fiction. It just took me a long time to admit it. So I thought about how to [tackle the topic] in a different way. And I came up with the idea of using a form of recorded conversation. So I came to my editor with this new idea, and it sounded good to him, and we went ahead with it.

The topic of life under a totalitarian regime resonated with Czech readers. Is it because we have our own experience of totalitarianism, even if not in such a harsh form?

After the publication, I received hundreds of reactions – both from the professional community and from the public. I was pleased that positive reactions came from both sides. I guess there was a memory of the past that needs to be revived, because we quickly forget what life used to be like. The younger generation was interested in the topic for a change because of their lack of direct experience of totalitarianism. Readers may also have found the text easy to read, but this has also been criticised. I don't interpret in the book; I don't impose my opinions, I let each reader make his or her own mind up. I was surprised to hear from a rather large group of former communists who felt the need to tell me that they were glad I was not condemning anyone in the book. They got the feeling that because of this they could stand up for their past... But that's certainly not what I meant!

|

Testimonies about life in North Korea Nina Špitálníková began recording interviews with North Korean defectors in 2014. She first travelled to Germany to meet them, and later to South Korea. She made contacts through non-profits that help refugees. For security reasons, she often had no idea who she would meet. As she was studying Korean studies, she wanted to know what life was really like in the DPRK. Authentic interviews were to help her find out. Publishing her findings in book form was not the initial purpose but later was buoyed by a hughely successful crowdfunding campaign on Hithit. |

A major theme you touch upon is the position of women in society. Even in the 21st century, it still doesn't seem to be easy in the DPRK.

And I'd say things have improved in recent years. When I visited the country in 2011, women were not even allowed to go to the pub. Their status has changed because they are more economically independent. The strictest rules are in Pyongyang, where women are not allowed to ride bicycles because it is not compatible with the requirement to be beautiful and presentable. But in villages, women could not get by without bicycles. Similarly, it was previously unthinkable for a man to appear anywhere with a mistress. Today, however, a mistress is a sign of status for men higher up on the social ladder.

What bothers women the most? Is it fewer rights, the lack of hygiene? Something else?

The lack of rights doesn't bother them much because they don't know anything else. There are still remnants of Confucianism ingrained. On the contrary, they find it strange that we can divorce or have multiple partners. North Korean women mainly deal with practical things – like the lack of feminine sanitary pads. When they menstruate, they have to change their cotton cloths, but they don't dry out when they are very wet.

An issue that recurred in all the interviews was in the military, where sexual abuse is very common. The woman either accepted that she was just a kind of object that men were allowed to do what they wanted with, or she felt an inner dissatisfaction that something wrong was happening and the regime should intervene. Which, of course, mostly didn't happen... For me personally, it was very unpleasant when women described how they were raped and how they still lived in fear. When we discussed military service in subsequent conversations, I was already stressed in advance about what I would hear again. The absurd thing is that they had all looked forward to their service because they are brought up to believe that it is a privilege. But then comes the sobering up - and they experience hell.

There's a very powerful moment in the book when an interviewee admits that after the death of her third child, she was actually kind of glad to have one less mouth to feed.

That moment took me a very long time to process. But the more stories one hears, the more it seems normal. I guess you turn numb after a while. Nowadays I try not to judge the respondents; but I am still unable to identify with anyone, for example, who left their children behind in North Korea in order to escape.

For me, the most powerful story was that of a student who had been a member of North Korea’s privileged or “golden” youth and had had a good life. However, her parents tricked her into being smuggled into South Korea, thinking they could secure a better future for her. But she was unhappy because she lost her privileges.

This conversation also hit me the hardest, I was not mentally prepared for it at all. For the first time, I met someone who missed North Korea and hated her parents because they had shipped her to the South. At the same time, I felt sorry for the girl, because from her point of view, her life was full of injustices. This story shows that even in North Korea there are citizens who are very well off; not all North Koreans suffer. Of course, I wondered about who her parents must have been to have afforded such a high status. It turns out that the “golden youth” there sometimes dare to rebel and have tattoos, hairstyles other than the official ones allowed, or have access to foreign fashion magazines. Some information was completely new even for me. For example, I had no idea that plastic surgery or various beauty treatments were also available in North Korea.

Will this rebellious generation not be a threat to the North Korean regime, if they want more Western-type lifestyles?

It is true that ideology was very much present in the older generation, while capitalism and the desire for goods were much more prominent in the younger generation. Think of what it was like in socialist Czechoslovakia or the Soviet Union - we too longed for Western goods. I think that this economic driver can be really powerful, maybe even more so than the human and political one. The regime can be swayed by the fact that even the upper echelons of society are now suffering from a lack of variety of goods due to the pandemic. Kim Jong-Un himself has admitted that the country is in a bad way and that “belt tightening” lies ahead – rhetoric that was used in the 1990s.

What is keeping you most busy now? Do you have another book in the pipeline?

I'm thinking of using the money left over from the Hithit fundraiser to pay someone who can get to Asia to gather more interviews. Going to the Korean peninsula is unrealistic for me right now. I'm also thinking of translating the book into English. I would have to revise the introduction, however, because Americans who have no experience with totalitarianism have no idea what under-the-counter sales are, for example. I would have to explain many of the realities.

At the moment, my son and my studies keep me most occupied; I still have a few exams to pass and a thesis to finish my master's degree.

How difficult is it to study as a single mother?

Fortunately, I have an individual study plan and the teachers are very supportive. But of course I have to fulfil my obligations just like everyone else. The biggest problem for me is finding time to read. I'm very honest in my studies and I can't imagine going to an exam without having studied the prescribed literature. I guess it's age. I no longer think of studying as going to school to fulfil something, but doing it for myself. Studying gives me more than it takes away. It's rewarding for me. I need to be more than just a mom. That's why I'm thinking about applying for a Ph. D. - in historical sociology. Because I'm a bit of a graphomaniac, I believe I could collect a lot of interesting material.

| Nina Špitálníková |

| Nina Špitálníková completed her Bachelor’s in Korean Studies at the Institute of Far Eastern Studies, Faculty of Arts, Charles University. In 2011 and 2012, she participated in study stays at Kim Il-sung University in Pyongyang. She is currently studying oral history at the Faculty of Humanities at Charles University. She won the Magnesia Litera Prize for her book Testimonies of Life in the DPRK (NLN 2020). She previously published Between Two Kims (2017) and a thesis on propaganda in the DPRK (2014). |