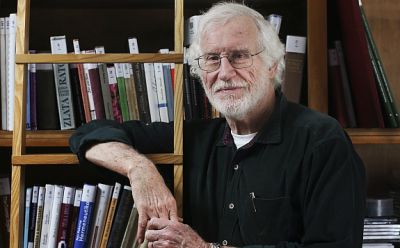

Thomas Hylland Eriksen is a world-renowned anthropologist whose research has taken him from the islands of Mauritius and Trinidad to Australia and back to his homeland, Norway. A professor at the University of Oslo, Eriksen is a prolific author, perhaps best known for the seminal Tyranny of the Moment: Fast and Slow Time in the Information Age (2001) and Overheating: An Anthropology of Accelerated Change (2016). The professor was honoured by Charles University this week.

Thomas Hylland Eriksen speaking at in the Grand Hall at the Carolinum on September 22, 2021, awarded an honorary degree for his life's work.

Professor Thomas Hylland Eriksen spoke to Forum about key facets of his career as well as how social anthropology has changed.

When it started out in the late 19th century, anthropology was of course almost a colonial venture. At the time, people went out to colonies to study “the natives” and there was a very asymmetrical power relationship between those who studied and those who were studied. But there was always a humanitarian approach in the sense that even in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, anthropologists really wanted to convey that different ways of life were not inferior, merely different. It was important to understand them on their own terms.

I began studying anthropology in the early 1980s and, at that time, we were still concerned with questions that are somewhat different from today. We studied people “far away” and we studied remote places, as it were. The mission of social anthropology then was to map and compare and to try to make theories about cultural diversity. Since then, there have been some changes. Back then, there was still a lot of emphasis on economies and politics and legal systems in traditional societies. Also in Western Europe, Marxism – Marxist-materialist approaches – were quite influential at the time.

After post-modernism, we began looking at other things: symbols, meaning, religion, ritual and identity. Identity came up in a big way: suddenly, questions of identity were all around us, as well as emerging nationalism. The end of the Cold War in Europe but also the emergence of various movements in the global south that emphasised the right to identity and the right to culture all changed the emphasis. Another difference today, is that anthropologists, increasingly, study “at home”. In the 1990s there emerged a big interest in comparative modernities, which is really what has been my focus. The study of societies that were influenced by the state, by imperialism, by colonialism and global capitalism and how those societies responded. How they are interconnected.

Some of the great growth areas now are in digital anthropology – the study of the smart phone, for example, how it is being used in rural China. The smartphone is the subject of my most recent book. Another big focus now is the Anthropocene family of questions: the way that humanity is altering the environment, climate change, and that kind of thing. So we have always responded to changes in the outside world.

Your early fieldwork was in two island states in different parts of the world: Mauritius, in the Indian Ocean, and later Trinidad, near South America and the Caribbean…

While I have done many things in my professional life but I keep returning to these Creole islands as I call them, which were shaped by plantation slavery, which are multiculturally mixed, where there is this strange kind of positive cultural creativity in terms of music, literature and art. There is a vibrancy in those societies and it continues to attract me. In Mauritius, a multiethnic society, I wrote about ethnic relations and the two largest groups there, the Hindus and the Creoles. The first are of Indian descent and the second of African and they are mostly Catholic.

I was studying the tension between the two: how it shaped their common identity, sense of nationhood and community, multicultural or even maybe a kind of post-ethnic identity that defined them as Mauritians.

A couple years later, I went to Trinidad, a country with a similar history also with two main groups: the Indo-Trinidadians and the Afro-Trinidadians. There were similarities but also differences, because Trinidad is part of the Caribbean world which is very much shaped by African and American and Black culture. Reggae from Jamaica, Calypso from Trinidad and the Blues from the Deep South in the United States. So there, the Hindus were a minority, whereas in Mauritius was the opposite and they are quite close to India.

So I was playing with that a bit in my comparative work. But I asked similar questions in Trinidad: what does it take to create a shared identity for people who have such different backgrounds and histories. One short answer is this: If you want to have a shared identity in a multicultural society, you should look to the future and not to the past.

Why is that?

Because if you look to the past, your shared past, you will discover that it is something you want to leave behind: it was Victorianism, slavery, colonialism. If you look to your own ethnic past what you discover is division, and diversity and boundaries and conflict and tension. But if you look to the future and say this is where we are, you can build a common future together.

You mentioned that more and more people are looking at the impact we are having as human beings, which you researched under a term you coined called “overheating”. Could you explain?

Overheating is accelerated change and we are living in a time when things are beginning to happen very fast: there has been an acceleration of acceleration, you might say. If you take something like tourism, we have seen tourist arrivals increase sevenfold in just over a generation: from 200 million to 1.4 billion between 1980 and 2019. Then there is the digital movement, which has also destabilised things, migration and also certain rights movements, which may make certain white men feel they are no longer as powerful as they used to be. In Great Britain, cultural theorist Paul Gilroy has written about the “nostalgic” mood and in the politics of the UK there is a very clear yearning for the simplicity and the hierarchies of the past.

You also had that in Trump’s America. Make America great again.

Yes, the nativism and populism seem to be part of a sort of seesaw movement or more fundamental political tension that we see all around us these days of a more cosmopolitan attitude versus a more nationalist, inward-looking view. A compromise in politics is needed to try to balance both sides because otherwise things could turn quite bad.

As I mentioned in the outset, when I was a student we were interested in class and economic differences but since then, there has been a general shift from class to identity and not just in anthropology but in the world. Within politics. You mentioned Trump’s America: there, it is not really about class, it’s not about inequality – he did nothing for the poor – but it’s about identity and race and to some extent gender. This is the kind of tension that I think we can see in many countries around the world, where you have a globalised, cosmopolitan openness on the one hand and a withdrawal into national identities on the other. The point is that there are good arguments on both sides so one project for the future could be to reconcile them.

In your reframing of globalisation through the lens of overheating, you describe crises in three areas. One of them is economic, the other ecological and the third, identity. In all three, there are tendencies or forces that run directly counter to each other. And it makes you think, things can’t continue like this. Constant economic growth runs counter, ultimately, to sustainability. They cannot both be maintained after a point.

That’s the big contradiction of contemporary civilisation. You really can’t have it both ways. Eternal growth is a mathematical impossibility and sustainability is hard to achieve if you want to retain all the spoils of modernity. It is very hard to get people to relinquish rights that they acquired over the years, such as the right to a comfortable life. I live in Norway, where we really live these contradictions in a big way. There is a wish to be sustainable, to take responsibility for the planet, for the ecology, for future generations. But the immense wealth we enjoy in Norway is due to North Sea oil and gas. So again, maybe there is some hope in finding some reconciliation [as a way of moving forward: the inward, local nationalist way of looking at things and the more globalised, cosmopolitan outlook.

During the Covid pandemic, I am certain many of us thought maybe this would open a window of opportunity because everything had to slow down, and that was fascinating to watch. Because suddenly acceleration stopped. Until then, between 2004 and 2019, the number of plane tickets sold in the world more than doubled: from nearly two billion to more than four-and-a-half. Many people in this part of the world would say it was the result of the Chinese middle class beginning to travel and that is part of the story but it is not the whole story. Everybody flies more than they used to. From one month to the next last year, air travel decreased by more than 90 percent. It was that dramatic. We could use this opportunity to rethink globalisation and conduct a kind of sorting exercise: which parts of globalisation do we want to keep and which do we want to slow down and reduce.

Maybe the answer is to prioritise, to be more concerned to with where our food comes from and to start to produce locally. Some of the countries where I work have put forward such initiatives. Maybe, in one way at least, the pandemic would be a blessing in disguise. There isn’t just one way: because there are so many different countries many will take a certain approach and others will look for different solutions.

In affluent countries like Norway things changed: we didn’t have oil in the 1970s and we did fine. We didn’t take as many vacations but we did take a holiday once a year and maybe stayed longer. So today, we could do less and do it more slowly. That is one of the messages that paradoxically came out of the pandemic from our governments: stay at home, do less, be less productive, don’t move around, the opposite of what we’ve been told for the last 40 years. De-growth is essentially what they told us to pursue and – in retrospect – maybe it wasn’t such a bad thing to slow down.

The other thing we need to do is scale down problems to levels that are manageable. I can’t take on global warming and the damage to the glaciers in Greenland or Antarctica on my own. Does that mean I should do nothing? Probably not. And there probably is something I can do, locally, where I live, at home. I can save this clump of trees, or this stream, or get involved in recycling plans, or vote for Green Party candidates at the municipal council, or push for more biking lanes and fewer parking spots. We can act where we are. If you slow down, it won’t make you feel less happy or that you’ve relinquished something. I think it will give the opposite: the feeling that you’ve gained something, which is time.

You’ve said in past interviews that anthropologists have to like people (obviously, laughter) But in this accelerated time prior to the pandemic we would often complain when we had to go somewhere or see someone, at least at times when things piled up. Yet Covid lockdowns made us realise how much we need each other.

I think so. The metaphysics of absence made itself known in a very acute way during the pandemic because all of the things you took for granted were not there anymore. That’s when we realised how important they were and how much they mattered to us. So I still believe that this civilisation will take a slightly different course. Not immediately, because as the situation improves, people will want to run out and catch up and release this frantic energy that is built up. But maybe after a year or two they will think about everything that happened and with all the climate agreements that countries have signed, maybe this could be an opportunity to do something.

On a different tangent, you have been coming to the Czech Republic for a long time and you are familiar with the Czech mentality. Did you ever think about the Czechs as a subject for an anthropological study?

There are lots of things about Czech society that have interested me and I have had students who did fieldwork here. One was here in the early 2000s who studied hacker communities. Czechs have always been strong in the natural sciences, others have written about national identity largely because of the transition period after the Cold War. One of the things that interested me as a Norwegian is the structural relationship of the Czechs and the Slovaks compared to the one between the Swedes and the Norwegians. Because in a certain sense, the Czechs are the Swedes and we are the Slovaks.

The Czechs were urban, they were sophisticated, the Slovaks were peasants, a bit romantic, a bit backward and it was the same between Sweden and Norway. You have mutually intelligible languages that are so close they could be considered dialects of the same language and there is this asymmetrical relationship. In the Norwegian/Swedish context, since we don’t go to war with each other anymore, we face off on the sports field. For us it’s mostly alpine and cross-country skiing, while for you and the Slovaks it’s ice hockey. So there are these structural similarities.

But there is also a lot more because there is also a complementarity. In Norway, we have a lot in the way of new money, but we don’t have a lot of history. Yes, we have the Vikings but they were a peasant society. Whereas, the Czechs don’t have as much monetary wealth but have this deep cultural history which makes you feel, when you walk the streets here, that you are part of a long story about Europe.

It wasn’t always harmonious, it was full of friction and conflict and suffering but also of beauty and insight and cultural wealth. I felt very strongly when I first came here in the 1990s that I was part of a story that I hadn’t earned… but I nevertheless felt grateful to be a part of. This story about Europe.

Now that story has continued at Charles University, in the Grand Hall of the Carolinum. Congratulations.

I am grateful and honoured. Charles University is one of the great institutions of learning in Central Europe. [It was] a fantastic occasion and a big day for me.

| Professor Thomas Hylland Eriksen, Dr.h.c. |

| Thomas Hylland Eriksen is Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Oslo. His textbooks in anthropology are widely used and translated, and his research has dealt with social and cultural dimensions of globalisation, ranging from nationalism and identity politics to accelerated change and environmental crisis. He is currently writing about the effects of overheated globalisation on biodiversity and cultural diversity. |