“God or fate or history willed that I become a doctor here without having studied properly here...,” are memorable words Václav Havel said in his thank-you speech after receiving an honorary doctorate in the Great Hall at Charles University’s historic Carolinum building in 1990. Havel was the first person to be awarded the doctorate on the free soil of the university after the fall of communism in Czechoslovakia.

Václav Havel (front row, second from left) receives his honorary doctorate at the Carolinum at Charles University in 1990. Photo: CU archive.

“He had an amazing gift of artistic intuition and especially of language, he could express ideas in a unique way. He combined bravery and human wisdom with personal courtesy, shyness and modesty,” says the priest, theologian and professor at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University Tomáš Halík, who was Havel’s long-time friend. Halík and fellow Czechs who knew Havel either personally or as a public figure – president, dissident leader or playwright – will be remembering the statesman and his legacy this week; Saturday, 18 November, marks the tenth anniversary of his death.

Václav Havel never gained a university education. Under communism, he was not allowed to attend any university of the humanities, and he did not complete his studies at the Czech Technical University He did not officially enter Charles University until he became Czechoslovak President in 1990. He valued his honorary doctorate immensely. "All my youth I dreamt in vain of becoming a student of this most famous Czech university. My mother dreamt to the end of her days that I would receive a doctorate from it... Our country will inspire others if it is inspired itself. It is the task of educators, and therefore of this university, to inspire. It is a great honour and a great commitment for me to continue to consider myself a part of it as a holder of its honorary doctorate,” he said.

Tomáš Halík spoke to Forum about Mr Havel, widely regarded as one of Czechoslovakia’s finest presidents - a man who through his personal bravery and writings inspired many worldwide.

When did you first meet Václav Havel?

When I was still a boy, Václav Havel - as a young student still unknown to the public - was at our home and asked my father, the editor of the writings of the Čapek brothers, to consult him about the writings of Josef Čapek. I don't remember our very first meeting, but both my father and then Václav Havel told me about it when we celebrated my fiftieth birthday together. My father often recalled what a modest and well-mannered young man he was.

And personal meetings that you remember? What were they like?

I visited him in the fall of 1967. At that time, on the eve of the Prague Spring, I founded the first student debating club at the Faculty of Arts at Charles University, and after the editors of Literary noviny were fired, I invited them to take part in a discussion with students. Václav Havel was very interested in the atmosphere among the students and that's probably where our almost 40-year friendship began.

Václav Havel with Tomáš Halík. Havel went from playwright to imprisoned dissident to Czechoslovakia's first post-communist era president.

Did you meet regularly?

In the 70s and 80s I gave several lectures at his request in the residential seminars in his brother Ivan's apartment or at Jitka Vodňanská's. Havel also sometimes visited our seminars at Radim Palouš's apartment in Kampa - it was there, at a Christmas party in 1989, that the idea of nominating Radim Palouš as the first post-Soviet rector of the Charles University was conceived. When Václav Havel became president, I became a regular participant in the "Friday debates" at the Villa Amálie in the park of the castle in Lány, and one of those to whom he sent his important speeches, especially those for foreign countries, for comment and remarks. Havel thus continued the tradition of Masaryk Fridays at Karel Čapek's villa - in a room I admired as a boy when my father regularly held talks there with Olga Scheinplflug, Čapek's widow.

What did you help him with?

Two meetings with Havel were particularly fruitful. In the turbulent days after the Velvet Revolution, on 23 December I brought Bishop Jaroslav Škarvada, who had returned from exile in Rome for Christmas, to the centre of the Civic Forum. With him, shortly before - on the occasion of the canonization of Agnes of Bohemia, when I was allowed to go to the West after 20 years - I had visited Pope John Paul II in person for the first time and was able to tell him a lot about the “underground church” of which I was a part, and we also talked about the possibility of “rehabilitating” Jan Hus [The Czech religious reformer who was burned at the stake in 1415 for heresy, some one hundred years before the time of Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation – ed. note].

At that meeting - a few days before the presidential election - Václav Havel said that he would be very happy, if elected, to invite the Pope to Czechoslovakia, if possible to calm the atmosphere before the first free elections. Bishop Škarvada argued at the time that such invitations had been planned and prepared for several years. However, immediately after his return to Rome he was again invited to dinner with the Pope and told him about our meeting and Havel's proposal. To his surprise, the Pope replied, “Why not? But first I have to get an official invitation.”

So Bishop Škarvada immediately telephoned me and the very next day I went to Prague Castle to see the newly elected president, and the same day the official invitation to the Vatican went out. Then I was invited by the Pope to go to the Vatican right away, and I spent five weeks there preparing the visit with the pontiff. The historic first visit by John Paul II to our homeland and the first visit by the pontiff to the post-communist world then took place in April 1990.

Did Havel manage to surprise you in any way outside of state and political affairs?

I remember that during the [clandestine] residential seminars and also during the debates in his cottage in Hrádeček he followed the lectures and discussions extremely closely and, as always, got the most important things right. Then, after the revolution, I recognised the echoes of these debates in his state speeches and lectures abroad. He had an amazing gift for artistic intuition and especially for language, and he could express ideas in a way that was unorthodox. This is also why he was a shining star among professional politicians producing platitudes.

Was there anything that you disagreed about?

When we were discussing the draft of his famous speech welcoming the Pope at Ruzyně airport, I managed to persuade him to leave out one problematic phrasing. Then, during a stormy meeting of the wider club of advisers at the Villa Amalie on whether Havel, or rather the Czech Republic, should support [George W.] Bush's invasion of Iraq, I was one of two who were against it.

What made Havel so original?

By combining bravery and wisdom with personal courtesy, shyness and modesty.

What idea of his could be applied to the present? What could we learn from him?

Many things. For example, that “truth and love” - a phrase now ridiculed by the followers of lies and hatred - are not dirty words, but the very foundation of a free democratic society, its ethical biosphere. That the constant humble questioning of where the truth lies and question one’s self whether they [might be] wrong is not a stalling of political and economic processes by idealistic dreamers, but a prevention of grave mistakes with fatal consequences. That democracy is not just a political system to enforce a majority opinion, but a culture of interpersonal relations, requiring a culture of law and respect for minorities.

If you had a chance to say something to him now, what would it be?

To intercede with God on our behalf.

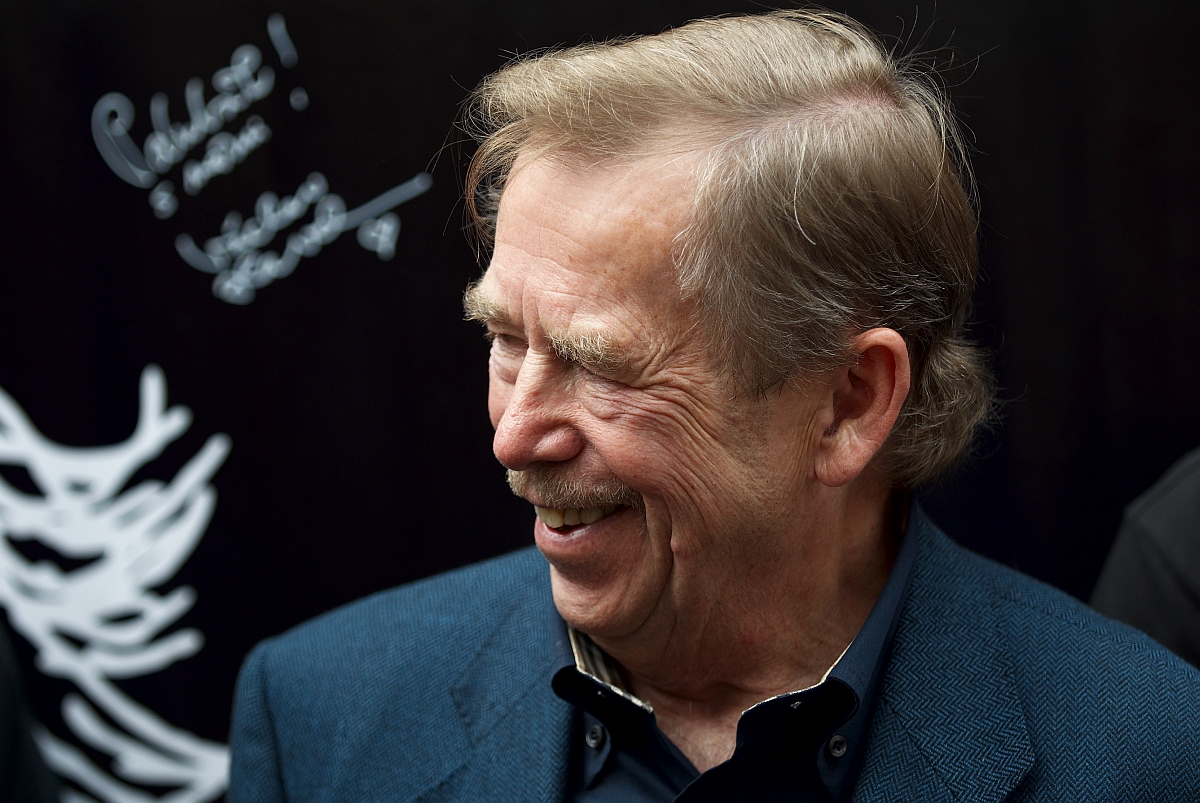

“[Havel] combined bravery and wisdom with personal courtesy, shyness and modesty,” says CU's Tomáš Halík.

In 2013, Charles University founded the Václav Havel EUROPAEUM MA Programme. It was a student exchange programme opened for students in the academic year 2012-2013 by the Department of European Studies of the Faculty of Social Sciences and is run under the auspices of EUROPAEUM, an international association of leading European universities. In addition to CU, its members include the University of Oxford, Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, Leiden University and others. The Václav Havel EUROPAEUM MA Programme is designed primarily for Master's degree students in International Area Studies (NMTS) with a specialisation in European Studies and Western European Studies, but also for Master's students with a European focus in general.

Václav Havel and his first wife Olga in 1990. Havel last visited the Carolinum in 2009, when Adam Michnik received an honorary doctorate.

In his memory, Charles University also provides financial support to foreign students whose studies are made difficult or impossible by repressive, totalitarian, authoritarian and other unfree regimes around the world. The Václav Havel Scholarship can only be awarded to a student who has been admitted and enrolled for study at one of the faculties of Charles University on the basis of an admission procedure.

| Professor Tomáš Halík |

| Tomáš Halík is a Czech Catholic priest, theologian, philosopher and sociologist of religion. He lectures at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University. Since 1990 he has been the president of the Czech Christian Academy and the rector of the Church of the Most Holy Salvator in Prague's Clementinum. Since 2004, he has also been the pastor of the newly established Academic Parish in Prague for teachers and students of universities. He studied philosophy and sociology at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University and was a pupil of Jan Patočka. During the communist period he was active in religious and cultural dissent, and in 1978 he was secretly ordained a priest. He worked as a corporate psychologist and psychotherapist for drug addicts. After 1989, he travelled widely, including as a visiting professor at Oxford, Cambridge and Harvard universities. Pope John Paul II appointed him advisor to the Pontifical Council for Dialogue with Non-believers (1990), and Benedict XVI made him an honorary papal prelate (2008). In 2014, his life's work was recognized with the Templeton Prize, and in 2016 he received an honorary doctorate from Oxford University. His most recent awards - the title of honorary professor from the International Institute for Hermeneutics at the University of Warsaw and the Józef Tischner Prize - were awarded this November. |