It was a formative experience that opened a gateway into another world. Shortly before the Velvet Revolution, when he and his brother were boys, his parents brought home a samizdat translation of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. They began reading the book aloud to their sons at bedtime. They probably didn’t expect it would change Jan’s life. Influenced both by the genius of the author and his literarily and spiritually inclined parents, Jan A. Kozák went on to study at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University, where he now teaches and specialises in Norse mythology and myth theory. Alongside the structured, precise world of science, he freely lets his imagination roam when creating the fantasy realm of Qurand - the setting of The Saga of Lundir, his debut work of fiction, for which he won a Magnesia Litera award in the fantasy category.

“My mum is an antiquarian, we always had loads of interesting books at home. But when my parents got hold of a samizdat (self-published illegal) copy of The Lord of the Rings, it was something extraordinary. We never had medieval manuscripts at home, but this was something similar—just from the 1980s, typed on a typewriter, a blurry nth-generation copy. They read it to us like people read the Bible. I was captivated by Tolkien’s escapism and the feeling that normality is, at its core, oppressive—but through a barred window, one might still glimpse a radiant world. It was a secret book that no one else had at the time, yet it was ten times better than anything else. That’s when I said to myself: I’d like to one day awaken in others what The Lord of the Rings awakened in me.”

There and back again

J.R.R. Tolkien took Jan A. Kozák to a world from which there was no return—a world of fantasy. He even jokingly refers to Tolkien as his “third parent.” “I didn’t start writing straight away. As a child, I used to draw various labyrinths and design board games. When I was about 13, I had a high fever and found myself in a world that offered me a welcome escape from my illness. It became my safe place, around which my fantasy world began to crystallise,” recalls Kozák who choose the fictional name Alatyr to distinguish himself from namesakes. Alatyr is an Old Slavic and Old Russian distortion of the Greek name for amber—a legendary stone from which rivers are said to spring, and which fascinates him.

As a secondary school student, he read not only fantasy and sci-fi but also Carl Gustav Jung, Ladislav Klíma, and Friedrich Nietzsche. His father was interested in Eastern philosophy, and they studied Sanskrit together. Naturally, this led Jan to the Faculty of Arts at Charles University, where he focused on Latin and religious studies. He became increasingly fascinated by ancient languages, learning Ancient Greek and Biblical Hebrew, before turning his attention to Northern Europe and learning Old Norse. Eventually—like his spiritual forefather Tolkien—he fell in love with Norse myths. He also took up historical fencing and today even runs his own fencing school. As a stunt-fencer, he appeared in Juraj Jakubisko’s epic film Bathory.

“I spent many years studying dead languages. Even while reading academic literature or listening to lectures and making notes about Roman religious practices, my brain would run parallel fan fiction. I’d immediately start imagining what it would be like if the Romans had a different culture—what if, for example, the Vestal Virgins weren’t just one cult among many, but the central one? That’s how fantasy worlds form in my mind—worlds rooted in reality. This is how I function all the time. I let myself be ‘possessed’ by a ritual or symbol and in my imagination I let it blossom, reveal its hidden potential,” he explained. He devoted his dissertation to Óðinn, one of the chief Norse gods, and later published it as a monograph. He began to explore myth theory and its interpretative history in detail. Not long after completing his doctorate, he moved to Norway, spending two years at the University of Bergen. There, under a prestigious Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions fellowship, he worked on the Symbodin project, which explored bodily symbolism and metaphor in Norse mythology. He also drew inspiration from the Nordic “fertile emptiness,” as he calls it.

Today he teaches at the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies at Charles University. Alongside ancient myths, he also studies modern ones—conspiracy theories and pop culture, which he calls the myths of the 21st century. In 2021, he co-founded the research group Conspirituality, whose aim “is not to debunk conspiracy theories but to understand how they form and function, much like religion scholars do with faiths and mythologies,” as explained on their website.

“I Want Old Myths to Be Alive”

For him, the worlds of science and fantasy constantly intersect. Where science confines him with strict theoretical boundaries and demands objectivity, the fictional world allows his imagination full rein. “My problem is that I want myths to be alive. We study them as dead specimens behind glass. One mustn’t interfere with them—must stay objective, consult only preserved sources, and then attempt to interpret the myths cautiously through complex theories. I understand that we must avoid wild interpretations and be able to distinguish what is actually in the myth from what we merely want to see. But I really wish these powerful, potent stories had a more vivid connection with everyday reality—and that it were acceptable to dream them onward, to continue them.”

Thus, alongside the exacting world of academia, he gradually created his own world full of legends and magic, where he or those who join him set the rules. He named it Qurand, and it draws inspiration not only from Tolkien’s Middle-earth but also from Persian and Indian traditions—and, of course, from Norse mythology. For a time, it existed only through the website Siranie.net, maintained by Kozák and a group of collaborators, named after one of the lands of Qurand.

The World of Qurand

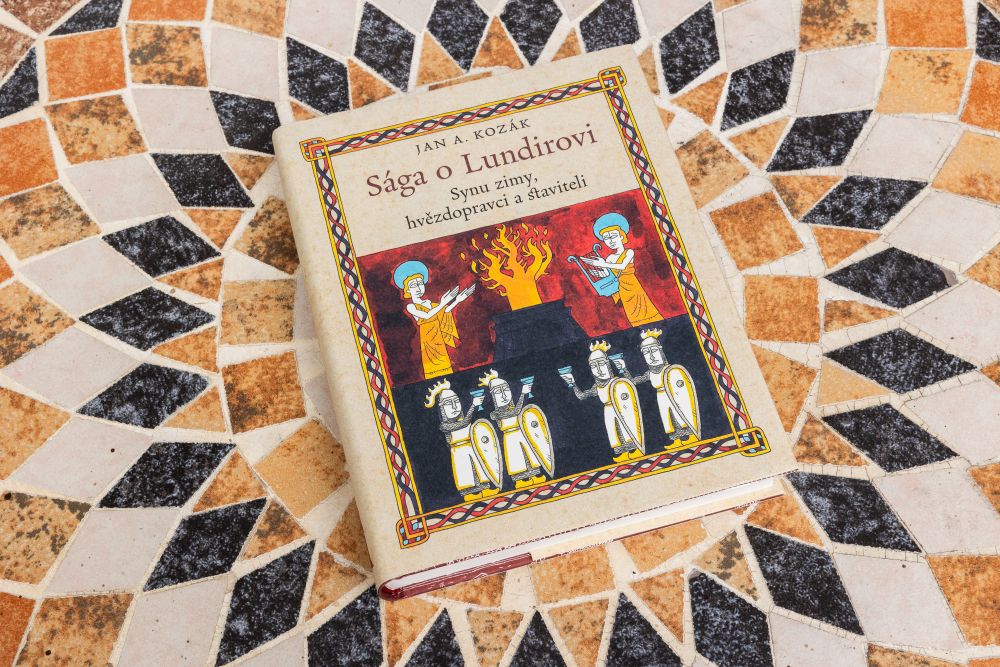

Kozák eventually began writing—not for publication, but privately. Encouraged by a friend, he shared his writings with a publisher. The result was The Saga of Lundir: Son of Winter, Stargazer and Builder, published by Malvern, which unexpectedly earned him the Magnesia Litera for fantasy last year. During the awards ceremony, he was so shocked and emotional that the host, Daniela Písařovicová, offered him a hug—which he gratefully accepted with a laugh.

The Saga of Lundir introduces readers to a meticulously developed world populated by humans, elves, wizards, and various dark creatures. Part encyclopaedia, part fictional narrative, it includes an inserted map and academic-style commentary. Kozák does not appear as the book’s author but—as a nod to Czech humourist Jára Cimrman—as its translator and scholarly annotator. The ruse worked so well that some bookshops and libraries filed it under “myths and legends” or even “history.” Kozák is able to imitate the saga style perfectly, thanks to years of study. In fact, he prepared and annotated the first Czech translation of the Saga of Hervor.

The Saga of Lundir is nearly a bibliophilic edition, with beautiful illustrations that evoke medieval illuminations. Jakub Hruška and Jiří Karban, who also help run Siranie.net, created the artwork. “I’ve always liked collaborating on projects. So even The Saga of Lundir is the result of teamwork. I gave Jakub sketches, names of things, and notes about the look of towns and places—he did the rest. Much of it is his own work. Jiří is fascinated by medieval illumination. He chose what to illustrate and how, and I wrote the accompanying commentary. We think this collaboration works wonderfully. I like how the story comes alive—so much so that sometimes even I don’t quite understand what’s going on!” he says.

Czech fantasy author Lucie Lukačovičová has also been inspired by the world of Qurand, writing a number of short stories set there. “It’s another collaboration that worked brilliantly. I hope it continues this way. Anyone who wants to get involved is welcome. I don’t guard my copyright too tightly—I enjoy mutual inspiration. After all, mythological worlds once worked like that—there were several versions of every story, each told in its own way. The important thing was that the image came alive!”

Although Jan A. Kozák continues writing academic texts and is also undergoing psychotherapeutic training—both of which demand a lot of his time—he is working on further instalments set in Qurand. “The seeds of the next saga are already sprouting. Jiří Karban is even illustrating it. So we’re probably not leaving this world any time soon. I’ve also sketched a story about a small village where people worship fire. Readers won’t be quite sure whether the setting is fictional or real—perhaps a strange cult in our own world. But I definitely won’t go the route of typical fantasy, of which there’s far too much these days. I want to keep experimenting with style!”

| Jan Alatyr Kozák, Ph.D. |

| Jan Alatyr Kozák is a graduate of the Faculty of Arts at Charles University, where he studied Latin and religious studies. He currently teaches at the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies, specialising in pre-Christian Scandinavian religion, myth theory, and its interpretive history. He also explores modern mythologies, conspiracy theories, conspirituality, and pop culture. Thanks to a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions fellowship, he spent two years at the University of Bergen, and later also studied at the University of Iceland. He is the author and co-author of several monographs, including Óðinn: Myth, Sacrifice, and Initiation (2018) and Monomyth: A Synthetic Treatise on Myth Theory (2022). He prepared the first annotated bilingual Old Norse–Czech edition of the Saga of Hervor. He also translated The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún and The Fall of Arthur by J.R.R. Tolkien into Czech. His debut novel The Saga of Lundir won the Magnesia Litera award for fantasy. He also practises historical fencing. |