Olga Kotková has been surrounded by Old Masters like Cranach, Rubens, and Škréta for more than 30 years. Since graduating from Charles University, she has worked as a curator at the National Gallery and is now the director of the Old Masters collection. Not long ago she finished preparations for a large and extraordinary exhibition titled Women Artists 1300–1900 now open at the Waldstein Riding Hall in Prague, which shows how women succeeded in asserting themselves in the traditionally male art world across centuries, and what themes they brought into art.

When did your interest in art begin?

My mother took me and my sister to theatres and galleries frequently. At first, we found it boring (laughs), but a summer job at 16 in the regional galleries department of the National Gallery changed everything. Initially, I wanted to study biology, but that summer job made me decide on art history, instead.

Why did you start your doctoral studies at the Faculty of Education 20 years after graduating from the Faculty of Arts?

At the time of my first studies, I earned the PhDr. degree (a doctoral-level certificate), which was enough then. After university reforms, a full PhD became necessary to lead scientific projects. With two small children, I postponed my studies, but after they started school, I studied Czech and Slovak history at the Faculty of Education. This combination has proven valuable in my work.

What exactly does a curator of the Old Masters Collection do?

Contrary to popular belief, it’s not just walking around looking at paintings. The work involves expert research, managing and administration, including legal matters and sometimes even building maintenance — for example, preventing leaks. Curators prepare catalogues, organise exhibitions, and accompany artworks during transportation, often spending hours on trucks or airplanes to ensure the safety of the pieces.

What is something unexpected that can happen during transport?

Paintings usually travel by road, and sometimes trucks break down. The art must be stored temporarily in controlled conditions. During air transport, curators or restorers must be present to ensure careful handling, sometimes even catching crates just before loading. During the pandemic, remote monitoring with cameras was introduced.

How do you approach understanding old paintings?

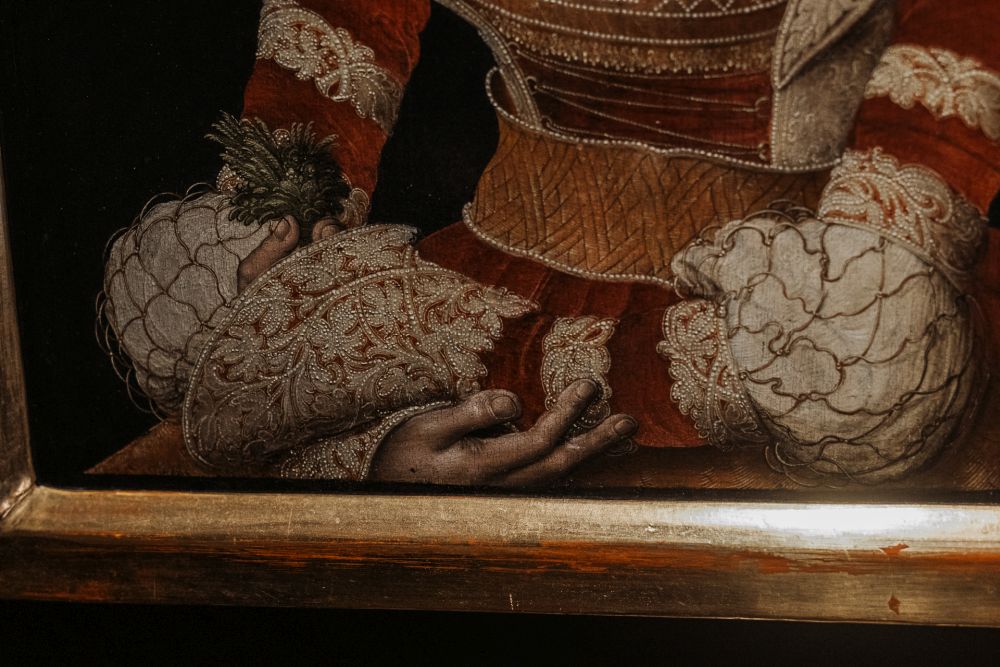

You need to study the historical context, artistic techniques, themes, and the environment of the period. Details matter: the hands in paintings are especially telling, because the master usually painted faces and hands himself, while the workshop painted the rest. The backs of paintings can also reveal clues, such as signatures or changes made over time.

Why are you so interested in the hands of the figures in the painting?

Painting a good hand is a true mastery. Usually, the master himself painted the main parts—especially the face and hands—while the rest was done by his workshop. When I see hands that look rubbery or as if the figure is wearing gloves, I immediately think the workshop was involved, or that the entire painting might be a workshop piece. It also makes me wonder whether it could be a later copy or even a forgery, which sometimes appear even in old art. However, I avoid using the term “forgery” until restorers and chemists have examined the work.

I expect that you work a lot with specialists?

You’d be surprised how many people I’ve worked with. Besides the restorers and chemists who work here at the gallery, I often have to consult experts from other fields. For example, a key procedure in Dutch art research is dendrochronology — a scientific method for dating wood based on tree ring analysis. But we also consult specialists about the subject matter of a painting. For instance, in our collection, we have a portrait of a musician with musical notation visible in the background. Since it’s a Dutch painting, I reached out to several musicologists and eventually to Professor Ignace Bossuyt from the University of Leuven, who was able to pinpoint the exact five-year period the notation corresponds to.

When I was preparing the exhibition of Roelandt Savery, a painter who worked for Rudolf II and depicted various animals, colleagues from the National Museum helped me a lot. I especially needed bird specialists, since his paintings feature many parrots and cockatoos. I also consulted entomologists. We often collaborate with botanists, fashion experts, historians, and specialists in historical objects, daily life, or applied arts, who can tell you when and where certain items—like the dishes shown in a painting—were used.

It almost sounds like detective work…

When I was preparing the exhibition of Lucas Cranach the Elder, I also worked with a painting from our collection that shows a girl staring blankly ahead, holding a green plant in her hand. Nobody was quite sure what to make of it, and some even said that Cranach—or any good painter—would never have painted it that way. So I started investigating. I found out that the portrait was created by mechanically transferring the girl’s likeness from a drawing onto the painting using tracing paper. What stood out was the girl’s vacant stare and the plant she was holding. My experience told me that the plant was the key to understanding the painting. That’s why I reached out to the Berlin botanist Eckhard von Raab-Straube, who also studies the history of botany and medicine. He explained that it wasn’t an ordinary fern but a resurrection plant (Selaginella lepidophylla), which has a remarkable trait—it withers when dry but turns green again when watered. Bingo!

It was a reference to resurrection. The portrait was painted after the woman’s death as a memorial. The plant symbolised eternal life. This explained her empty gaze as well. Such a small detail became the key to understanding the entire work. Every art historian must constantly seek answers. It’s very rare that a painter would include something randomly in a painting. This mostly happens with copies, when the copyist doesn’t correctly understand an originally meaningful element. Objects and plants depicted in paintings almost always carry significance. The people who commissioned paintings in the 16th and 17th centuries were highly educated, and this was reflected in the artworks.

How do you update the Old Masters for a contemporary audience?

Old art is primarily about interpretation. An exhibition must be expertly curated but also tell a story that engages the public. If you just hang a few old paintings on the wall, no one will come. Sometimes, though, it’s a real challenge.

I believe that a large state institution like the National Gallery should not give up on specially targeted exhibitions that, in turn, attract great international attention. A good example was our Roelandt Savery exhibition. When foreign galleries organize shows including his works, they still consult us to this day. Thanks to efforts like this, the National Gallery recently participated in the Rudolfine Art exhibition at the Louvre in Paris. Globally, the National Gallery is relatively small, but through such projects, we place ourselves among the top-tier museums, like the Louvre.

This time, you are building a story around women artists. What can we expect from the newly opening National Gallery exhibition?

You probably noticed the posters for our permanent exhibitions, Old Masters I and Old Masters II, as you came into Šternberk Palace. I walk past them every day and often wondered, “Where are the female Old Masters?” The idea attracted so much attention that the National Gallery’s top management suggested the topic deserved a larger project. I accepted the challenge and prepared the exhibition Women Artists 1300–1900.

The life roles and paths of women artists were very complex, and they truly had to fight to claim their place. First, we want to show that female Masters existed and were perhaps overlooked. The National Gallery has extensive collections of Italian and Dutch art, so we chose to highlight the works of women from these regions and present the situation in Central Europe.

It is remarkable how active convent sisters were, creating beautiful works of art in monasteries. In contrast, it may surprise some that women in the Czech lands could not lead painting workshops. A woman could only become a master of a workshop if she was a widow. Official art education for women here only began after the founding of Czechoslovakia, when, around 1918–1919, women were first admitted to study at the Academy of Fine Arts. Some women even used male pseudonyms to avoid scandal while working. It was only at the end of the 19th century that female artists in our country ceased to be seen as curiosities and began receiving recognition.

We will also share some beautiful stories of women supported in their efforts by their families — support that was crucial for their work.

Which story of a woman artist featured in the exhibition is your personal favourite?

A real highlight is a painting titled The Chess Game, created by the Italian painter Sofonisba Anguissola from Cremona. Sofonisba came from a noble family — she had five sisters and one brother. Their father was highly educated and ensured all his children received a good education. Sofonisba wasn’t interested in marriage; she devoted herself entirely to caring for her siblings and to painting. Even Michelangelo admired her work. Later, she worked for the Spanish king Philip II, who held her talent in high esteem. He even arranged a marriage for her to provide stability so she could continue creating art.

We’ll be exhibiting two of her paintings. In The Chess Game, she depicts her younger sisters playing chess. What makes it so interesting? At the time, chess was considered an intellectual pursuit primarily for men. By showing her younger sisters engaged in the game, Sofonisba made a subtle statement — that even “little girls” could handle something intellectually demanding.

For our colleagues in the natural sciences, not just at Charles University, it will surely be exciting to see works by Maria Sibylla Merian at the exhibition.

Yes, and near her work, we’ll also be exhibiting a piece by Rachel Ruysch. Both of these women came from intellectually rich families—Rachel’s father was a renowned botanist. Maria Sibylla Merian had an insatiable thirst for knowledge, which led her all the way to Suriname, where she studied exotic plants and butterflies. We’ll display a beautiful edition of her illustrated book on caterpillars, loaned by the Moravian Museum. She was both an artist and a scientist, merging artistic sensitivity with analytical rigor.

The Netherlands in the 17th and 18th centuries was remarkably progressive in this regard. Leiden University, with which both artists were connected in various ways, had a stellar reputation in the natural sciences. It was an era of overseas expeditions. Every time ships returned, they brought back exotic flora and fauna, and people would flock to the harbors to see them. Sadly, most of those animals didn’t survive long because people didn’t yet know how to care for them properly—but this only fueled the hunger for knowledge even more.

Do you surround yourself with art at home as well, or do you prefer bare walls to rest your eyes?

I often visit exhibitions even in my free time, but I’m very selective. I’m also careful about what I allow into my own home — no oil paintings are allowed there! (laughs) I have some beautiful old prints, a stunning antique map, and a drawing by a contemporary Dutch artist. At home, I also pay close attention to lighting — no direct sunlight on anything!

But when I really need to clear my head, I go to the mountains. There’s nothing more beautiful than looking out over the snow-covered Alps or the Krkonoše (known as the Giant Mountains in English).

| Olga Kotková, PhD |

| Olga Kotková studied Aesthetics with a focus on Art History at Charles University and defended her dissertation on collecting German and Austrian paintings from the 14th to 16th centuries at the Faculty of Education in 2013. She has been a curator at the National Gallery’s Old Masters Collection since 1990 and its director for three years. She specialises in German, Austrian, and Dutch painting and sculpture from the 15th and 16th centuries, as well as Rudolphine and Flemish painting of the 17th century. She also lectures on Art History at the Catholic Theological Faculty of Charles University. |

In Forum magazine, we write about Charles University graduates. But graduation is not the end! Stay connected with your alma mater and remain part of the Charles University community through the Alumni Club.