Biologist Petr Pyšek is the proud holder of the prestigious Czech Head award recognising his life’s work. He received the award in 2022 for the study of invasive organisms. “Invasive ecology is a field that examines how humans spread plants and animals around the world and guages what their impact is on nature,” he explains.

Petr Pyšek is a co-founder of modern invasive ecology, the creator of the global database of invasive plants, and the author or co-author of hundreds of articles in expert journals. He has received numerous awards and is currently one of the most cited invasive biologists in the world. Students at Charles University can run into the scientist either at the Faculty of Science or at the Botanical Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic in Průhonice near Prague, where he heads the Department of Invasion Ecology.

Professor, what was it like to receive the Czech Head?

Do you mean in terms of the live television broadcast? I'm more of an introvert by nature so I initially felt a little out of place. But everyone was very kind and helpful and it was fine. I am fortunate to have received several significant awards during my scientific career, including the Neuron award [in 2018] or the International Biogeographical Society award [in 2021]. I value them all greatly, but I consider the Czech Head the highest recognition as it is a domestic award. Hopefully, it will raise public awareness of biological invasions and how problematic they are.

Do you expect the award to spark not just awareness but a deeper interest?

The award may not change all that much as we've already been working towards raising interest in invasion ecology for some time. I believe that public awareness, whether among experts from other fields or laypeople, is relatively good in Czechia. It's more about the fact that an award like this and the associated publicity can help draw attention to the fact that what's called “green biology” has its place among modern scientific disciplines, and the topics studied by invasive ecologists are important. We continue to make progress in the field and the organisms we work with need to be well understood.

Is it correct to say that modern invasive ecology is about more than “a thistle transported accidently in someone’s clothes to the other side of the globe”?

It is [but that is also a part of it]: there are of course studies about how non-native species ended up in Antarctica on hikers' clothing. It might sound like a mere curiosity but it illustrates the fact that nowadays invasive plants can be found practically everywhere. Simply put, invasive ecology is a field that examines how humans transport plants and animals around the world and the consequences it has for nature. We're interested in who, when, how and why, as well as how often, these organisms were introduced into the environment.

To understand invasions, it's necessary to look into the past because what we see today is the result of processes that began decades or even centuries ago. We need to understand species and their populations, including their characteristics and responses to changing environmental conditions, but also where they invaded and where they are native, where they originated. Therefore, it's essential to understand related aspects of human behaviour because those too are crucial for invasions. Only when all these pieces come together can we make reasonably reliable predictions about the potential dangers posed by the introduction of plants and propose practical steps to manage them.

Where did invasions begin?

The origins of invasions can be traced back to the heyday of colonial powers when people brought their animals and favourite plants, especially crops, to newly discovered or conquered territories. They wanted to feel at home. Today, we talk more about invasive science than just invasive biology or ecology because we rely on a wide methodological apparatus, which, in addition to biology, also includes social and economic sciences. It's exciting trying to find common ground, especially when different fields often speak different languages.

You must enjoy writing… you are the most cited invasive biologist in the world.

I do, but even if I didn't, I would still consider writing a duty. Doing things just for pleasure and not publishing them is too costly for science and we are paid, after all, from public funds. Our most cited article to date is from 2000, where we described the conceptual framework for invasions, proposed a classification of the invasion process, and terminology. Thanks to the acceptance of our approach by the scientific community, standardised data collection on invasions began. About a decade later, we were able to start building, with seven colleagues from Germany, Austria and the UK, the global database of non-native plants, GloNAL (Global Naturalized Alien Flora). I deliberately created this acronym to resemble the name of a Tolkien's dwarf. Gloin sounds the closest but in fact, no such dwarf exists.

The database we established has become a milestone in the study of plant invasions. In our texts, you'll find not only descriptions of general principles but also extensive global-level analyses, and these articles are cited much more than works on individual plant species. As for the high citation rate, it's because our field has experienced significant growth in the last 20 years, and almost every ecologist, botanist, or zoologist eventually encounters invasions in their work.

Given that your father was the renowned Czech botanist Antonín Pyšek, did you really have a chance to pursue any other field?

The truth is when you see a deep passion for nature from a young age, you don't really consider anything else. I observe this in my four-year-old grandson Matyáš now, who is curious about everything in nature. We all have a close connection to nature: my daughter is a zoologist, my wife is a landscape architect, and I am a botanist. The link goes back even further: my grandfather was the head forester for Count Kolowrat.

Therefore, you too were influenced, in a non-coercive way…

Non-coercive… you could say I ended up in botany mainly because at one point I felt a bit sorry for my dad. He made a significant effort, taking me into nature, teaching me how to find my bearings and see connections, urging me to learn about plants. Like most children, though, I was more interested in animals as I had fish and turtles that I cared for. But at the age of around 14, I told myself I would make my father happy and learn to determine a few plants which I thought would satisfy him and that would be the end of it. However, because I am at heart a collector, I began my own herbarium and starting keeping records of all my specimens and plants I have seen. That was how I started.

Later you and your father became colleagues in the field – that must have been very special.

In the 1970s, after the crushing of the Prague Spring, my father was fired from the Faculty of Education in Plzeň, where he had been teaching botany. He joined the company Stavební geologie (Building Geology), where he worked alongside hydrogeologists to detect and trace the direction of contamination in oil or gas leaks. My father became a pioneer in this field, one of the first in the world to identify the direction of spills by studying symptoms in vegetation, observing changes in colour, vitality, or the presence of certain plant species. After graduating from the Faculty of Natural Sciences at Charles University, I joined him in this work for seven years. I have fond memories of working together.

What about the influence on your daughters?

It's nice to have a good relationship with your own child and a common professional interest. With my daughter Klára and other colleagues from the Institute of Botany of the Czech Academy of Sciences and the Faculty of Science at Charles University, we initially worked in Africa on a biodiversity project. In Kruger National Park, we studied the effect of seasonal rivers on the maintenance of species richness in the plants and animals of the African savannah. We cooperated with ornithologists, entomologists, one group studied bats, Klára used camera traps to record mammals. This monitoring is still going on, for five years now. The uninterrupted recording of animals that are found in an area about the size of a quarter of the Czech Republic is already becoming quite unique due to the length of the monitoring period. My older daughter, Bára, is a physiotherapist, so she too has not escaped the family biological tradition, although she has gone her own direction. She is the mother of two boys, with the older one I mentioned I could have quite ‘sophisticated’ discussions about dinosaurs.

Where and when have invasive organisms directly “crossed your path”?

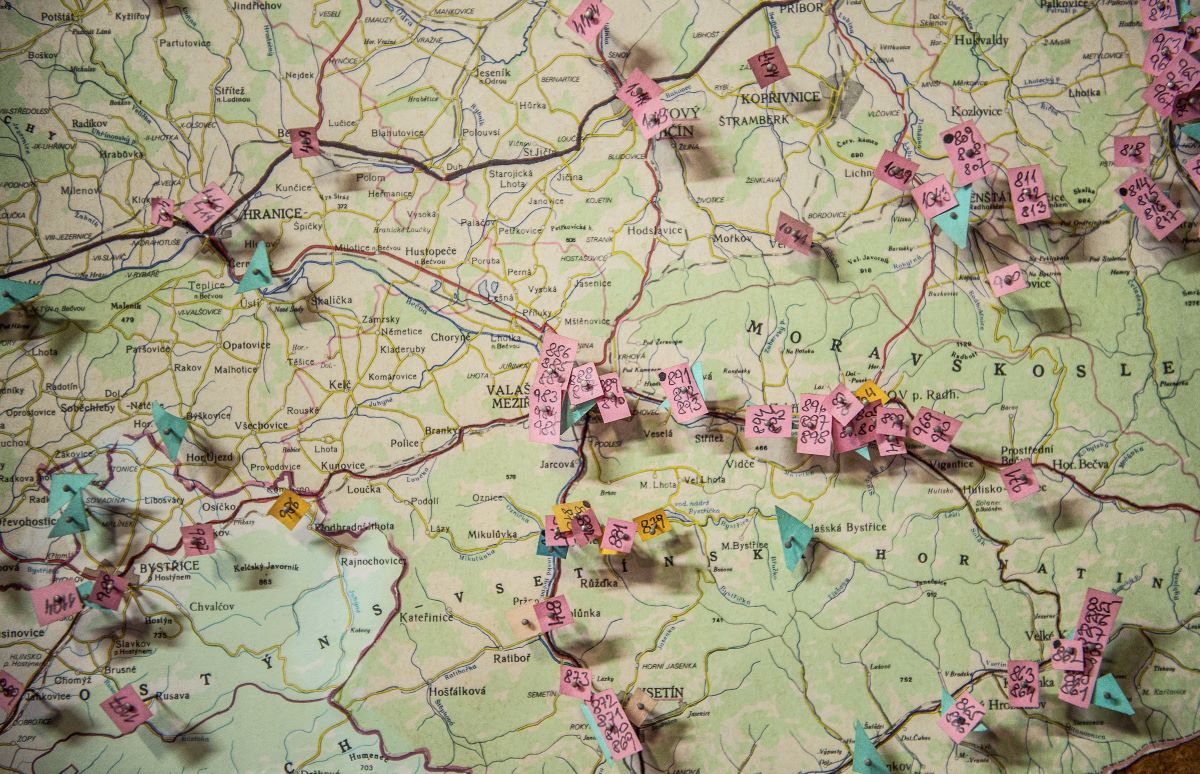

Back when I was working with my father, when we were focused on something fairly routine. You know the giant hogweed? It's easy to see from a distance, often growing along the road. We began to record its presence during our travels until we managed to map it all over the Czech Republic. When I visited Oxford University in 1991, I met people who were working on invasive plants. Two years later, we organised the first conference on invasive plants in Kostelec nad Černými lesy, where I was working at the Institute of Applied Ecology of what is now the Czech University of Life Sciences. The event later formed the basis for regular meetings. They are still held at two-year intervals in various places around the world today.

Is there anything to like about hogweed, really? The Metternichs are said to have planted it in the park at Kynžvart castle because it was so unusual.

How the giant hogweed came to us from the Caucasus is not fully known and might never be fully answered. We have a general idea but a few pieces of the story are missing. The plant is undoubtedly impressive, it is the largest herb growing in Europe. Is it truly ugly? It's pointless to foster negative emotions towards plants: they just do as they can.

“The Return of the Giant Hogweed” is also a song by Genesis from 1971. I know you are fond of music: if you could grab a beer with any musician, would Peter Gabriel – as an amateur invasive biologist - be one of them?

There would be quite a few but Peter Gabriel is one of my lifelong favourites. I thanked him in a section of my master's thesis because I had listened to a lot of the early Genesis albums, right up until he left to pursue his solo career. [The Return of the Giant Hogweed] very aptly describes the history of the invasion of the hogweed. When we published a European monograph about hogweed in 2003, we used excerpts of the lyrics as epigraphs for each chapter.

| Professor Petr Pyšek |

| Petr Pyšek is a graduate of the Faculty of Science of Charles University. He studied geobotany at the Department of Botany and heads the Department of Invasion Ecology of the Botanical Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences, which he founded in 2004, and also works at the Department of Ecology of the Faculty of Science of Charles University. He is one of the founders of modern invasion ecology, a co-author of the conceptual framework of invasions and classification of the invasion process, and co-founder of the global database of invasive plants GloNAF (Global Naturalized Alien Flora). |