A major success: Charles University’s First Faculty of Medicine is receiving its first prestigious European Research Council (ERC) Starting Grant. It was awarded to Slovak biophysicist Andrea Gálisová, who, after completing her doctorate in Prague, also worked at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, from 2018 to 2022. As an imaging methods expert, it was there that she came across her current research topic: extracellular vesicles, which until recently were considered a kind of “cellular waste.” What is it? Why are these particles interesting?

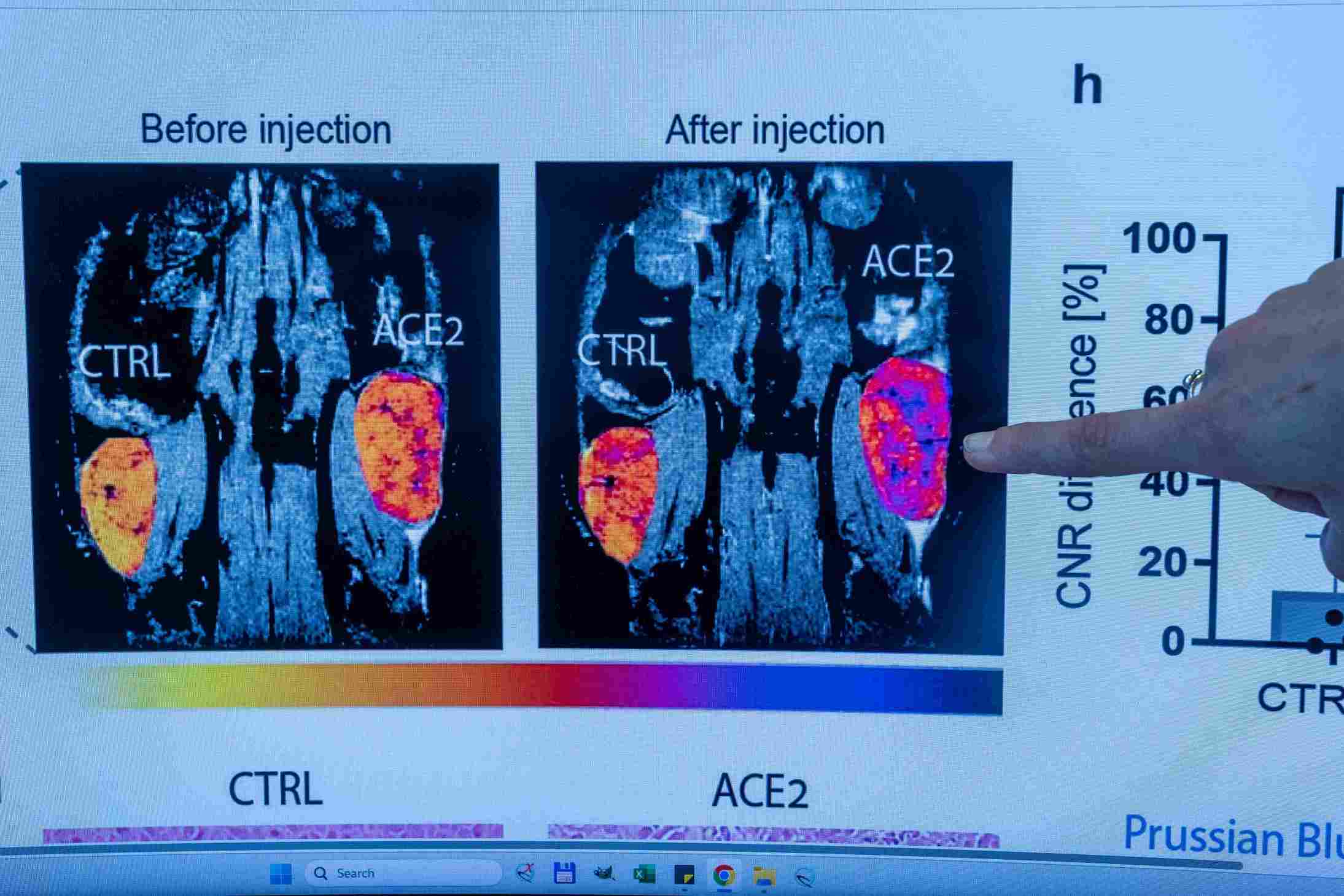

“Extracellular vesicles are small sacs made up of cell membranes that serve for intercellular communication. In our project, we will modify them using molecular biology methods so that they can deliver drugs, imaging agents, or membrane proteins to selected tissues and cells in a targeted manner. We will also monitor the modified vesicles in a living organism (mice) using the state-of-the-art heteronuclear magnetic resonance method,” explains Gálisová, describing the contents of her ERC project.

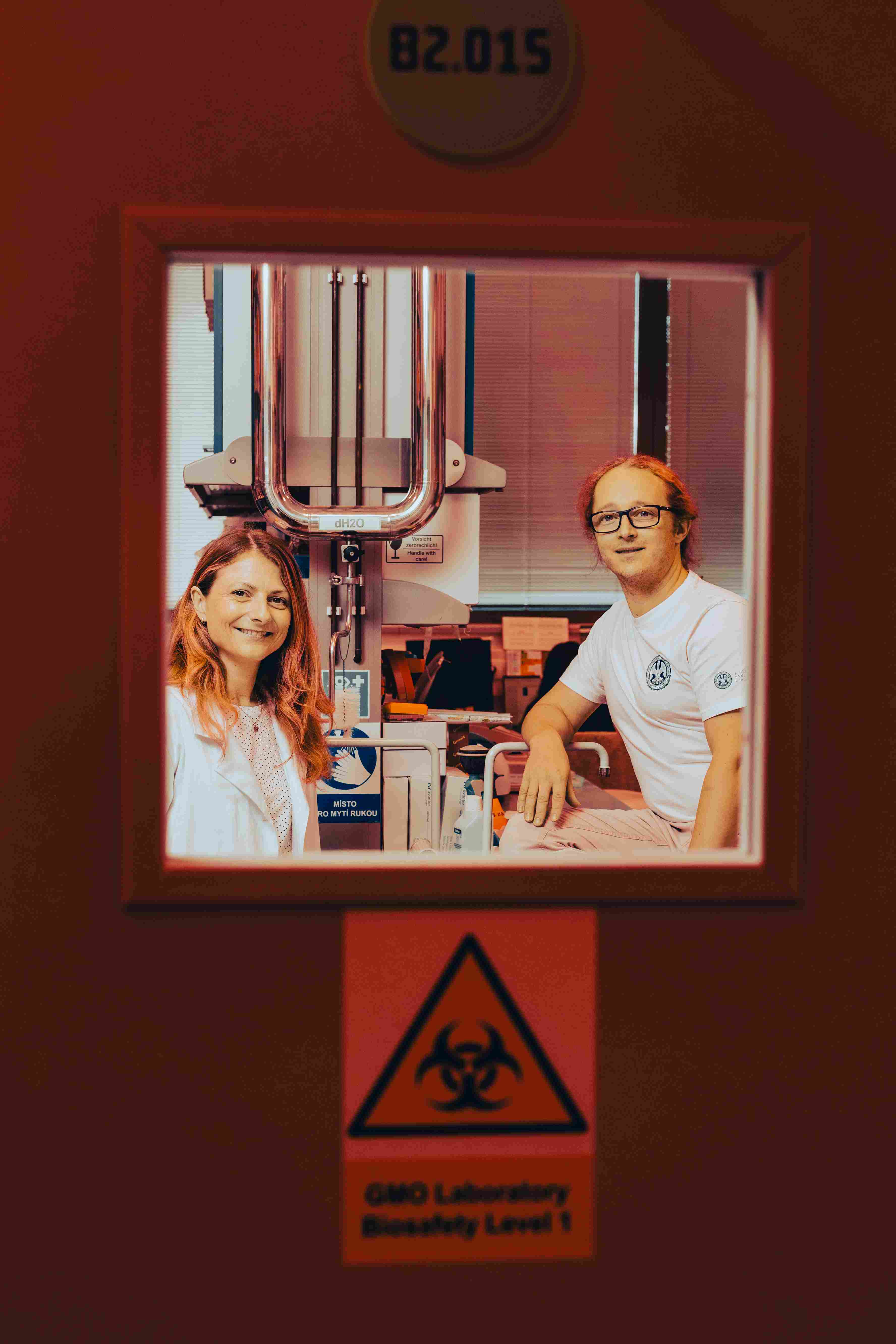

She currently works at the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine (IKEM) in Prague’s Krč district, where implements imaging methods for visualization of extracellular vesicles in mouse models, and at the BIOCEV research centre in Vestec, which is a joint facility of Charles University and the Academy of Sciences. Gálisová is a member and associate scientist of Jiří Zahradník’s Laboratory of Protein Engineering. The great atmosphere at the workplace, as experienced by both at the Weizmann campus, is confirmed by the label on the door of one of the laboratories: among the many titled academics is a certain ‘Dr. Peter Venkman’ – yes, the scientific star of the hit comedy Ghostbusters (1984)! However, Gálisová’s research is no longer mere science fiction.

Congratulations on receiving the ERC Starting Grant. It is a demanding and highly competitive competition. Could you briefly introduce your project to our readers?

First of all, thank you very much. My ERC project focuses on the creation and development of novel transport systems for delivery of therapeutics to specific tissues. I use extracellular vesicles for this purpose; these are small particles secreted by all cells in the human body that serve as a means of intercellular communication. We are trying to use these tiny vesicles to our advantage by modifying them appropriately so that we can deliver drugs or proteins with therapeutic effects directly to the tissues.

Will your research focus solely on this mechanism, or are you already targeting specific diseases that this approach could be effective against?

At this stage, I am more concerned with the platform – we are developing the entire system as a whole. However, I am focusing on cancer, specifically breast cancer, because it is a relatively simple and easy-to-understand model for basic research. Plus this type of cancer is widespread and it deserves our attention and searching for new treatment options.

Your work takes place at BIOCEV, but also at Krč’s IKEM. How do these two complement each other?

For the last three years, I have been working on my own Czech Science Foundation (GACR) project at IKEM, where I focused on developing methods for visualization of extracellular vesicles and worked mainly with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Now, with the ERC, I am focusing more on biology and protein engineering as well, so the next step is moving towards more biological research.

Would it be fair to say that your work combines the equipment and expertise of multiple institutions? On the one hand, there is fundamental research, and on the other, as it were, more targeted applications.

I would say it is actually a combination. Either way, this and that. The main reason why I stayed at IKEM as well is the opportunity to use special equipment for pre-clinical magnetic resonance imaging. It is not commonly available – it involves an extraordinarily strong magnetic field designed for imaging small animals. This most recent MR device is located in a small building at IKEM, which we call ‘the small house.’ It is literally a dream machine that we have been striving for for decades, and fortunately, Professor Daniel Jirák succeeded last year. It is a state-of-the-art scanner that can also perform heteronuclear imaging. This means that it not only displays water, as is common, but also other nuclei, such as fluorine. Fluorine is not naturally found in the body, so we can observe its signal very specifically. At the BIOCEV centre, we will mainly use basic research methods and equipment to study proteins and cells.

But the grant recipient is you and your home institution, the First Faculty of Medicine at Charles University, right?

Yes, the grant is administered by CU’s First Faculty of Medicine. We made an agreement that we’ll do the imaging measurements on the equipment at IKEM, but the main research will be done here at BIOCEV.

What shape will your ERC research team take over the next five years? Do you already have postdocs or PhD students working with you, or are you still looking for them?

At the moment, I already have one close collaborator – Dr. Jiří Zahradník, who specializes in protein engineering. We will need that. I will be recruiting students and doctoral candidates during the first six months, or perhaps the first year, of the project. I plan to hire two doctoral candidates, a postdoc, and several staff scientists. So yes, I am the principal investigator of the ERC project, but we will gradually expand our team to include specialists from related fields.

Are you specialised more in biology, or biophysics?

You could say that I am both a biologist and a biophysicist. I deal with magnetic resonance imaging as well as the study of extracellular vesicles. The topics we cover are highly interdisciplinary and require expertise in several fields. My colleague, Jirka here, helps me with the design of the proteins that we add to the surface of these vesicles to give them the properties we require.

Jiří Zahradník: It is mainly about modifying and adjusting proteins so that they are correctly presented and functioning optimally in the exosomal (a type of extracellular vesicle – ed.) environment.

As far as your team is concerned, who else do you need to bring on board and what expertise do they need to have?

I definitely need someone who is knowledgeable about working with extracellular vesicles, because it is a very specific field – and working with them is also technically demanding. I am also looking for students who already have at least a basic understanding of this field. Next, I need someone who understands imaging methods, working with small animals, as well as other experts in protein engineering. But I believe that a good student can learn the job even without prior experience.

Will you also work with animal models?

Yes, the entire platform will be developed at BIOCEV. This is a large biological project involving classic laboratory work, protein engineering, and the like. But once we have the final product, we will test it on mice using MRI at IKEM.

I assume that, given the prestige of the ERC grant, obtaining high-quality candidates for collaboration will not be a problem. Will you advertise new positions in professional journals?

I plan to start with European portals for researchers, such as EURAXESS, which are linked to the European Union. There, students and researchers can easily find interesting offers, and we can really pick the best candidates. Plus, we’ll try through the websites of scientific societies and, of course, the BIOCEV website.

Jiří Zahradník: If I may add, we are already receiving emails from applicants, often from the United States, because the scientific environment there has been changing a lot recently... It is a difficult situation for many scientists who often find themselves without the funds to continue their research. We are collaborating with a colleague whose grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have been terminated. He is an immunologist, and it is precisely in the field of immunity in women and men, where they talk about “gender,” that there has been a debate about the verbiage, as if certain words were inappropriate, which the (Trump) administration is very attentive to, and so language can easily become an obstacle to research.

“It was wonderful to work in an environment where you don’t have to constantly think about whether you have the funds for all your experiments,” Gálisová reminisces on her Israel experience.

So, your team will be international, and in fact, thanks to the two of you – a Slovak and a Czech – it already is…

(laughs) It definitely will be. That is very important to me – having a diverse environment where different people bring different perspectives, experiences, and ideas. In fact, that is already the reality we live in today.

Jiří Zahradník: Although we have one Czech member in our team (Martin Mokrejš), Prokopios Andrikopulos is from Greece, Adam Hruška is a Slovak student, and our doctoral students are Aditi Konar from India, Bailasan Haidar from Lebanon, and Ruojin Tian from China. We also have Oleksii Redchenko, who is originally from Ukraine, on our team. Such diversity is a huge asset.

You both have experience from the Weizmann Institute. What did you take away from your time there?

It was an incredible experience. The institute’s equipment is first class, with the best instruments available. Everything is concentrated on one beautiful campus, which is very well interconnected on a small site. If you need to measure something, you just walk a few steps to the next building. They also have one of the world’s best “magnets”.

There is more freedom there. It was wonderful to work in an environment where you don’t have to constantly think about whether you have the funds for all your experiments. We weren’t forced to publish an article every year just to “tick a box” on our report card. Not to mention filling out timesheets (smiles). It was more about doing high-quality, outstanding science – and the results then came naturally.

Jiří Zahradník: It is also thanks to this that there is a great willingness to cooperate there. The atmosphere is just open and wonderful, with people genuinely helping you, and it is not as competitive as elsewhere. The important thing is the common goal of being the best. The place simply has it!

Jiří Zahradník: It is also thanks to this that there is a great willingness to cooperate there. The atmosphere is just open and wonderful, with people genuinely helping you, and it is not as competitive as elsewhere. The important thing is the common goal of being the best. The place simply has it!

Have you found any glimpses of what you are currently working on with the ERC back in Israel?

Yes, it was precisely there that I began working with extracellular vesicles – until then, I had hardly known anything about them! But I have combined my original expertise in magnetic resonance and contrast agents with applications in this new field. I am very grateful to my mentors Prof. Amnon Bar-Shir and Neta Regev-Rudzki for introducing me to this field.

Jiří Zahradník: It’s been a big change for me too – I learned modern in vitro techniques of controlled evolution and their application to the study of protein interactions. I’m using all of that in our current research, and it will also be part of my own ERC proposal…

Don’t tell me you’re submitting your own ERC proposal too?!

Jiří Zahradník: Yes, I am preparing for submission, probably soon, as the deadline is in mid-October. It could complement Andrea’s work in some ways – it is naturally complementary.

Let’s go back to the ERC grant you have already obtained. What is your total budget and what will it be spent on?

The budget amounts to €1.8 million ($2.1 million). Approximately €400,000 will be spent on equipment.

What equipment will you be purchasing?

Primarily, I need an ultracentrifuge – this is the basic device for isolating and preparing extracellular vesicles, which is the cornerstone of my work. We will also purchase a “vesicle-counting machine” so that I always know how many tiny particles there are in the sample and can dose them accurately. And on top of that, a fluorescence microscope for observing cells and vesicles and to “see this beauty” in colors.

The project is scheduled to take five years. Aren’t you afraid that the selection and purchasing process will take longer than expected?

I hope it works out quickly (laughs). But if there really is a problem with procurement, we also have the option of using existing equipment at BIOCEV or IKEM, which is available here at the workplace. So, my research can start virtually immediately.

When will that be? When does your project officially start?

Next year, namely January 1, 2026.

What results do you expect over the next five years?

Our main goal is to develop a new platform – that is the be-all and end-all of the ERC project. We want to create vesicles with specific properties that will enable the delivery of proteins into cells. We have several sequential steps, each of which will be important… We will gradually label the vesicles with contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. And finally, we want to apply them to an immunotherapy model. Meaning that the “MRI colours” will confirm the delivery of immune cells to tumours. Of course, we would like to publish our findings in leading journals, but that depends on how successful we are.

Which journals are you targeting with your research? Possibly Nature, Science, PNAS, Cell?

It will probably be more suited to biotechnology-focused journals such as Nature Biotechnology or Nature Biomedical Engineering, as it concerns the development of a system platform. There are no plans for a classic “big discovery” of a new molecule; rather than basic science, it will be a methodological shift.

You have already hinted at the potential applications in immunotherapy. What benefits do you expect to see in, say, five to ten years? Will this lead to more targeted disease treatment?

I sincerely hope so. There are already initial studies, sort of early signs, showing that this approach could improve the treatment of diseases, especially in the field of cancer and immunotherapy. We would like to achieve a similar effect to that of current CAR-T cells. These work by removing the patient’s own cells, genetically modifying them, and returning them to the body. We would like to develop a cell-free method as an alternative that could achieve this effect through extracellular vesicles. This could be very helpful in cancer therapy; it is already used for blood malignancies, but new procedures are also being developed for solid tumours.

So, is this a platform that can also be patented?

Yes, I think so. There are several steps in the project that have the potential to be made patentable.

You mentioned that vesicles are very small and difficult to label. How do you intend to solve this?

That’s a big challenge. Usually, contrast agents only get inside when we disrupt the vesicle – for example, mechanically with ultrasound or electroporation. But that damages the vesicle, and the effect isn’t ideal. We therefore want to develop a new method using protein engineering – we will build specific protein channels into the vesicle membrane that naturally transport contrast agents inside. This will give us a completely new way of labelling vesicles for imaging.

Could you say there are countries stronger than others in the area of your research?

For example, in Sweden, there is a very strong group at Karolinska Institutet with whom we could collaborate in the future. They are leading experts in genetic modification of vesicles. There are several other excellent groups in Europe, including one in Iceland. I collaborate with this group closely.

Jiří Zahradník: There are genuine leaders in protein engineering in Europe and around the world – for example, the group led by David Baker, a Nobel Prize in Chemistry laureate (2024), who works in the US. Their results are absolutely unmatched, with the team working at the University of Washington in Seattle.

I assume you also meet with vesicle experts at conferences.

The community surrounding extracellular vesicles is relatively young – it has only been intensively growing over the last few years. Before that, vesicles were considered to be merely a kind of “cellular waste.” Today, we know that they are very important and useful. The community is very friendly and open to cooperation. Last year, we also founded the Czech Society for Extracellular Vesicles (CzeSEV), which connects various groups within the Czech Republic.

You work at CU’s First Faculty of Medicine. Do you also teach, or only do research?

Not yet, but I would definitely like to teach in the future. I do like teaching. It’s just that over the last three or four years, while I was preparing the GACR project and working on developing the platform, I didn’t have the capacity for it. But in the future, I would definitely like to devote more time to teaching at Charles University.

And you, Doctor, are you already planning your habilitation somewhere?

Jiří Zahradník: Not yet, but someday, hopefully. I already teach selected chapters of protein engineering not only at the First Faculty of Medicine at Charles University, but also at the University of Chemistry and Technology (VŠCHT). I enjoy it and would like to continue on this academic trajectory.

How did you even come to move from Comenius University in Bratislava to Charles University in Prague?

In 2012, I received an offer under the Marie Curie program, and I applied for the selection process. I knew that IKEM and the doctoral program at the First Faculty of Medicine at Charles University were working with magnetic resonance imaging and conducting interesting research in the field of contrast agents. That’s why I decided to come here for my doctorate.

Your ERC project will run for five years. How do you imagine the results will look? Which outcomes do you anticipate? Monographs or other outputs?

High-quality scientific articles are our priority – that is, of course, the basis. If we manage to file patents as well, it will be a great success.

How about a spin-off, like a biotech company?

There has already been one spin-off with a vesicle theme established in the Czech Republic – Terasom, which deals with exosome modifications. I think there is actually room for biomedical applications here.

Are you satisfied with the facilities you have at the CU 1st Med and at BIOCEV?

Scientifically, it’s excellent here. The combination with IKEM is fantastic, BIOCEV is very well equipped – we have state-of-the-art microscopes, flow cytometry, proteomics laboratories. The only thing we’re missing is a nicer outdoor environment – we could use a little more greenery and trees. We would often joke about how we miss trees (laughs, and Jiří nods in agreement). The facilities are perfect, but the environment around us could be more welcoming – not least to attract students.

You also praised the atmosphere on campus at the Weizmann Institute in Israel…

Yes, the campus there was beautiful and open, people would meet informally, for example over coffee, and this often led to new ideas! Something similar would also be nice here, but I understand how centres such as BIOCEV and the nearby ELI super-laser just outside Prague came into being.

Jiří Zahradník: An informal environment is important for science. People meet, discuss ideas with colleagues, and this can advance research. We sometimes see this as both a blessing and a curse – we have the comparison with an environment that was truly inspiring, and we know that things could be better here too.

Andrea, tell us, when you’re not in the lab, how do you relax? Do you rest?

Most often, I do yoga – not only do I practice it, but I also teach it myself. It is an important part of my life; it helps me clear my head and “reset” myself. That’s a great complementarity to scientific thinking. I also enjoy dancing and trips to nature.

Yoga tends to be perceived as a spiritual, esoteric discipline and an inner exercise. How does that fit in with hard science, biophysics? Do they fit together?

They literally harmonise! In yoga, we tune into a calmer state of mind, and in magnetic resonance imaging, we tune the magnet to the resonance frequency of a given substance. For me, yoga is a beautiful connection between body and mind. Physical exercise calms the mind as well, which is useful in everyday life, but also in science and research. In a way, it’s similar – for me, both yoga and science are about discipline, curiosity, and discovering possibilities. That’s what keeps me moving forward.

| Mgr. Andrea Gálisová, PhD |

| Researcher at Charles University’s First Faculty of Medicine and BIOCEV. She focuses on the development and application of magnetic resonance imaging for non-invasive monitoring of cellular processes and research into extracellular vesicles. Her research specialises in the development of magnetic contrast agents for imaging tumour tissues and improving targeted therapy. She holds a degree in biomedical physics from Comenius University (2012) and a PhD from Charles University and IKEM (2018). She has also worked in Austria and Israel, as a postdoctoral researcher at the elite Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot (2018 to 2022). Most recently, she received an ERC Starting Grant (section LS9) for CU 1st Med. She has over 2,100 citations, and in her free time, she likes to practice yoga. |