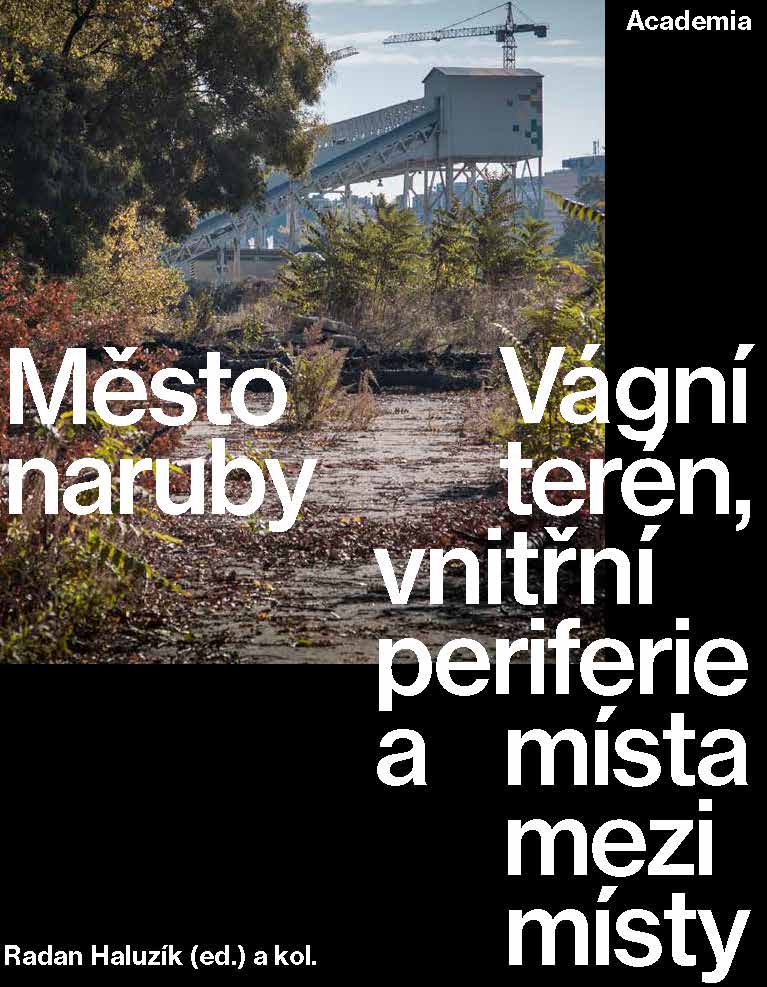

In French, it’s known as terrain vague – vague terrain, as in a wasteland or empty lot. But in reality it is any disused or largely inaccessible space, sometimes wild, sometimes industrial, where form and function stop. Mysterious, surprising, unknown. Social anthropologist Radan Haluzík and a group of fellow researchers and artists made vague terrain their subject of study for years. The result? The bestselling Město naruby (The City Inside Out), a fascinating monograph and multidisciplinary study published by Academia Press.

Social anthropologist Radan Haluzík, an expert on terrain vague in the Czech Republic, poses by a building that has seen better years.

Radan Haluzík, who edited the work and contributed several chapters, told me how it all began.

The project has deep roots going all the way back to the 1980s: a number of us, five or six, transferred to Charles University where we came in touch with Jiří Sádlo, who is a botanist, a poet and an important contributor and inspiration for the book who had connections to the school but didn’t actually teach there! He spent a lot of time in the outdoors, tramping through the Czech countryside and sleeping under the stars. He invited us to join him, so we’d grab sleeping bags and travel to places he carefully chose. That was the most important experience for us at that time.

His focus was ecological and informal, and eventually he began taking us into terrain vague or “vague terrain” around the Czech Central Mountains or the mining city of Most and into post-industrial terrain that had largely been abandoned. At the same time, he also gave similar excursions around parts of Prague. He’d point in a random direction and we would set out in a straight line and just keep going. If you reached a fence, you climbed over it. If there was a walled area with a guard dog, you went around.

For us, the post-industrial landscape was extremely ugly; at the time, we wanted to be in nature, in the wilderness, to visit national parks (laughs) but we ended up going to these industrial areas instead. That was the origin of our fascination and for a number of us it became a kind of hobby. A lifelong hobby.

What happened next? How did it go from just a hobby to serious research?

About eight or 10 years ago, we began to sense that something was going on, that there were various processes underway under the radar in the Czech landscape. We organised a small workshop and conference at the Centre for Theoretical Studies. One of the panellists (and one of the contributors to the anthology) Cyril Říha, a philosopher focusing on architecture and urbanism, proposed that what was going on were changes in the vague terrain. We followed it up with a second conference and the project began to take shape.

Soon after, we began getting together almost every month and more people, not employees of the centre, got involved. Colleagues, friends, spouses, scholars, scientists but also artists joined our group and what resulted was an 18-member collective of authors. We would go on excursions to diverse city areas together, we organised presentations and discussions and later we began writing. We then began sending each other articles for feedback and discussion and continued from there.

It sounds very “old school” in the most positive sense. The project seems to have taken on a life of its own.

It was definitely from the heart. There was no grant that would cover the work by all of us and more than half of the contributors did it for free. They liked showing up and taking part and they put in an enormous amount of work and did not get paid.

I am fascinated by some of the places and phenomena described in the book. When I moved to Prague I used to bike everywhere and came across really weird areas and at the time was at a loss to categorise what they were. Roads to nowhere; an abandoned factory; a fisherman’s house on a hill, miles from any river, with pike heads mounted on the facade.

The initial draw for us was also fascination and things like this pike house you mention… Fascination is great as a gateway but later it becomes a problem, scientifically speaking. You don’t want to end up in a swamp of exotisation. Fascination and romanticism are an important magnet to attract you to the topic but to get to next level we had to leave them behind.

Who were some of the scientists involved and what were their areas of expertise?

Those of us who were in the original group and had been interested in the typology of terrain vague had – in the meantime – each progressed in his or her respective fields: so, you have David Storch, who today is one of the world’s top macroecologists, published in Nature and other top journals. Petr Pokorný and Adéla Pokorná are paleoecologists, studying the past of European cities who also began studying the past of vague terrain. There is an archaeologist who is an expert on the Middle Ages, there is a philosopher of architecture, there is a social geographer, there are social anthropologists. I myself am a social anthropologist, one of my former students, whose focus is on life in Czech socialist panel housing blocks, is also involved. Some of us use the metaphor that vague terrain is a shadow of cities, its reverse side, and my wife, who is a Jungian psychologist who studied at Cambridge and Glasgow, took this metaphor seriously and made it the starting point for her own contribution.

Then, there is a group of artists who are also involved including the famous writer and poet Michal Ajvaz, who has been published around the world including the United States and Japan, conceptual artists like Epos 257 who creates numerous projects in vague terrain. There is a group whose members call themselves křovináři (thicketeers) who are often both artists and biologists who spend their time pushing through thickets and bushes. They call their activity thicketeering. They spend time there, test thickets, study what goes on and create diverse conceptual projects and makeshift galleries.

Then, there are those who are interested in the future of vague terrain: there is Štěpán Špoula, an urban planner and field architect from the Prague Institute of Planning and Development who writes about a new (more open and more wild) generation of parks in post-totalitarian Berlin, which could be a good example for our own post-communist Czech cities. There is an art historian. There is the aforementioned Jiří Sádlo, who surprisingly does not write about thickets and areas of underbrush, but how parks should be designed nowadays to meet modern day needs. That means a sophisticated mosaic of groomed spaces for play and rest, semi-wild places with some ecological and aesthetical management and some untended nature left to grow wild. Each of us has his or her own area of expertise and brings something unique to the table.

What is – and what isn’t – vague terrain?

It’s important to say that we didn’t work only with the term vague terrain (or terrain vague) but also something we called space within spaces. The dominant definition of cities is that they are functional. The city, as such, serves different functions, and in between there are “gaps” we don’t pay attention to very much. We see two ways vague terrain is formed: either municipalities or owners plant cheap lawns and plants around the area, the way they plant patches or small lawns around gas stations and highways and proudly call it landscaping. Or something spontaneous happens – an area is left unattended and weeds and bushes grow and it becomes vague terrain. Nevertheless, many lawns and cheap flower beds, if unattended, can also grow wild quickly and finally became vague terrain as well.

Those are gaps in a space, but even more interesting are gaps in time: land serves a function but it comes to an end. You can have, for example, a distillery in Prague Smíchov that closes down but it is not replaced overnight. Things take time. The land has to be sold, the old building torn down, a construction project paving the way for a new function should be prepared. Construction permits are needed, finances need to be raised, and in Central Europe this all takes at least seven or eight years and sometimes even longer. In the meantime, the place grows wild and we see a gap in time – vague terrain in time.

But these gaps in time can be far greater, lasting decades. I grew up on the periphery of the city of Zlín, where a sports centre had been planned and construction by the Baťa company began even before WWII. But it was never completed and it became kind of a spontaneous “wild nature area”, a childhood kingdom of unintended artificial swamps, lakes and bushes. We spent tons of time there as kids, playing and exploring nature, catching snakes and frogs. And the point is, that the sports complex was only completed around 1988! So that was a major gap of more than 40 years. In both time and space.

Another example is the family of Václav M. Havel (the father of the dissident and first post-communist president) built a luxury restaurant and public pool as part of the Barrandov Terraces project in Prague in the 1930s. Before it was a pool it was a limestone quarry, then after a 20-year gap it was a pool and it is no longer a pool again. Now it is a wild place, like in the story of Sleeping Beauty and it waits for its new function. So there are many temporal as well as physical gaps in the life of the city. The city pulses in its gaps.

There are signs of it all around. My wife and I have a “favourite” in the negative sense: an exposed brick building in the town of Miličín on the way to Tábor. It’s very frustrating to see. Never finished but standing there, exposed to the elements for years.

There is a much greater continuity, for example, in North America or Western Europe. Here, we have a much more marked discontinuity for political and historic reasons. Look at our recent Central European history and the second part of the 20th century! Jewish property was seized during the Second World War, then you had nationalisation after the war and after 1948,the seizure of Church property. And after that came the age of communist city planning with all those new towns built on the periphery of older ones. After 1989, you had post-communist era privatisation and restitution and the restructuring of the economy.

But because of 40 years of communism, we entered a new globalised economy late and a lot of things we were good at, from textile to car to steel production, had shifted elsewhere. So we have been through many, many changes and each change left a mark or even a gap in the city landscape. The result was empty areas, unused or used for something other than previously intended. Now that the wild 1990s of privatisation are behind us and the period of economic transformation is over, we began to have continuity again since around the year 2000.

Now, some of these forgotten areas are starting to be developed. Over the eight years since we started work on the book, a lot of vague terrain disappeared – for good or bad – and in cities we saw the rise of massive development projects. Cities are becoming more whole with gaps disappearing. That’s good but the bad is that these spots sometimes just become denser but without any thought for quality. In our book, we think these empty places are a chance to change the city for the purposes of the 21st century. To connect our scattered metropolises, to develop new local city centres and to connect old ones in our decentralised city outskirts, to build new parks, green pathways and green infrastructure. But the spaces will be filled either with offices or apartment blocks. The flora that was there will be wiped out. That’s the kind of period we are living in. We are wasting our historical chance to do something new. To renew the city.

Meanwhile, a lot of people who live in Czech towns and cities have gotten used to these spaces within spaces near their apartment houses or suburbs and are used to them and refer to them as “nearby woods” or “local nature”, and go for walks or exercise there. They bring a small keg of beer, sit around campfires making sausages, sometimes go on dates there or experience intimate moments, and the place serves multiple functions. And many don’t realise that this is vague terrain and they think that it’s a “public park” or just “nature” and one day the bulldozers show up. Anthropologist Martin Veselý in his chapter shows how local people can mobilise and raise their voices when their local favourite terrain vague is endangered.

You taught at New York University in Prague and at FAMU international – how is vague terrain different, for example, in North America where some of your students were from?

One difference is that such areas in the Anglo-Saxon world are, by law, very often fenced off. There can be holes in the fences but it is fenced off. Here, the line is more blurred because often there is no fence and no delineation. Is it nature? Is it a brownfield? Is it an abandoned park? Is it something else? You don’t know…

The other thing, I would say, is that here we are within the cushion of European welfare states. Even if we have a lot of homeless people on the street, social tensions don’t run as high. In Prague, there is practically no place a young woman couldn’t go at night. By contrast, in the 1990s, I lived for one year in Palo Alto in the US near Stanford University, a very expensive area of Silicon Vally, and when you crossed a little stream into East Palo Alto you entered an extremely dangerous area, where urban gangs operated in those times. Statistically, there was a murder each week.

When I asked some of my students if they had ever known anyone in any kind of youth gangs in the US, they burst out laughing. One of them, a student named Mike who was from Los Angeles, told me “That’s crazy, professor. Members of gangs don’t attend university!” and everyone laughed. Another student, Stephanie, who was from Brooklyn, described dangerous parts of the city she remembered from when she was a child. She said there was a part of town where “real gangs” operated and rape was common and no one in their right mind would go at night. This is another aspect of terrain vague in Central Europe: safety, social control. In Prague, you have places that, on the face of it, appear totally abandoned but the city still picks up garbage at wastebaskets there! And sometimes they leave the weeds but take the rubbish. So that is very different from the US, where, if an area has been neglected and there are weeds and garbage, it’s a good idea to stay away. Our country is very different in this respect. To conclude: the places we study are also shaped by safety and social control.

Do you have a favourite vague terrain?

I live in a part of Prague, which is right next to the historic centre, but where you have both a large river and high cliffs. The slopes of the cliffs are covered by bushes like somewhere in the Mediterranean and near the river are the last tiny bits of vague terrain shoreline like somewhere on the Amazon. A place where there is neither a path nor the river and for a long time a part of it wasn’t even on the map. It’s one of my favourite places and I go there once or twice a day when I am working from home. It’s only around 10 metres wide and several hundred metres long – a strip of trees and bushes alongside the river. The city started a drastic project of “revitalisation” by turning the area into an austere stone and concrete embankment. We got involved late, almost too late in communicating with the city, to ensure that at least the shoreline of this area would be kept as kind of a semi-wild park. And that could serve as an example of how to save other vague places.

There are NGO or even student projects to revitalise parts of vague terrain, for example, to use the area for pasture for domesticated farm animals. There are projects turning former industrial areas into wild parks.

Yes, in western European countries, such projects have been common for decades. I lived five years in London and saw disused railways or former industrial ponds transformed into kinds of vague parks. Nevertheless, by comparison, we have a lot more vague terrain here in Central Europe. And our wild places continue throughout the city: from its periphery almost into the centre. So these models are a good and challenging example, but not sufficient in their scale. A very good example for us is Berlin. Like cities in the Czech Republic, it inherited vague terrain. But Berliners dealt with such areas with democratic open-mindedness and encouraged a dialogue between all stakeholders. The city turned the enormous scar left by the Berlin Wall, that had divided people, into a kind of green centreline that became a new city axis and brought people together.

You mentioned that vague terrain areas in Prague or parts of the Czech Republic are generally not dangerous. Nevertheless, some of these areas hold up a mirror when it comes to societal problems, the most obvious being homelessness. My son often visits a skatepark at a popular Prague island, but in the underpart of the bridge he rides or walks over, there are sometimes quite surprising cardboard settlements. How do you look at that situation as a social anthropologist?

We are certainly not trying to idealise terrain vague, not by any measure. In the book, we deal with some areas as a kind of refugium for plants, animals and also people who have no room anywhere else. They are dodgy or sketchy refuges at best. Such spaces seem to offer hope of building a home there, but unfortunately, it is just a false hope, because anybody can come and destroy it. “Cardboard cities” can be dangerous and also precarious. The real owner can come and claim the space back at any time. What is interesting is the section in book by archaeologist Petr Meduna, that tells us that since at least the Middle Ages you had people who inhabited vague terrain. What is important to realise is that there was always a connection between marginalised people and marginalised parts of town.

Urban planning seems like an enormous undertaking and while so many solutions are needed, many unforeseen or unanticipated problems always arise.

Exactly. You want a city that is rational, with hygienically perfect norms, where everyone has enough sun and light, egalitarian access… But the result of such masterplans looking 10 years ahead, is that there is always something unexpected. We built, for example, grandiose projects of socialist blocks of flats for a generation of “new men” but got a city where youth become “urban savages” (laughs) who wanted to play in vague terrain, instead of carefully projected playgrounds and school stadiums. You got something no one foresaw. And that is how it always is.

You can try and pursue an urbanist dream but what you build always ends up functioning a little differently than you expected. We see a huge problem in urban planning and we think the field focuses too much on practice and not enough on theory. The field speaks very little about unspoken assumptions. It ignores the fact that every so-called urban masterplan has unintended consequences. The creation of vague terrain is just one of them.

We wanted to emphasise this in our book. We coined a term, in the beginning partly as provocation, but which I think needs to be taken seriously: inverse urbanism. Urbanism, where the empty spaces are as important as places with official functions, where the periphery is as important as the city centre. Urbanism, where the city hierarchy is seen from upside down. Or inside out. We need to look into the city from the point of view of the periphery, not just from the point of view of its centre. We need to know what surrounds functional places within our cities and why. Negative, seemingly empty, unused space is also space. And it lives its own (usually unseen) life. We need to be architects of emptiness. We have to consider the unintended consequences of our city projects.

I would still like to come back to some of the characteristics of vague terrain as “experience” because you also organise excursions. What are they like?

If you are walking through a city, you can always anticipate more or less what will be around the next corner. What kinds of streets, or even shops or tram stops you will see in a minute. Cities are regular and predictable. That’s not the case with terrain vague. In vague terrain there is a complete inability to foresee what comes next. And that can be refreshing. That’s what the artists on our team value so highly. It can be almost hallucinogenic or unreal. You come back from the field and feel changed somehow and it takes half a day for things to settle and return to normal. The same is true temporally: if you return to a patch of vague terrain after a month, the same area you saw recently may be different again. Vague terrain can be a place of very dynamic changes.

I took students from NYU onto one of the riverbanks in Prague and was talking about the unexpected and some of the boys complained “All we see are just bushes and piles of shit.” But then we climbed old steps in the middle of the bushes, which still had an original Art Nouveau railing! The steps were covered in brambles but we followed them up and suddenly out of nowhere – we caught sight of a modern office tower with a Ferrari parked in front! In vague terrain you never know what will be around the next corner: you can come across a fence, or an old aquarium with a plush giraffe toy inside, a campfire or a cardboard city with a portrait of Václav Havel! You just never know.

Another thing that we discovered was that it was almost impossible for us, even as researchers, to label or name such areas properly: it was always something like “the place beyond the tracks”, “the large bushes between the gas station and old brewery” – something between something. Spaces within spaces. Vague terrain remains hard to grasp and evades easy definition or categorisation. But there is also something refreshing about that.

| Radan Haluzík, Ph.D. |

| Radan Haluzík is a social anthropologist concerned with the relationship of politics and aesthetics, the social life of things and pressing global issues. He studied biology, ecology and social sciences in Prague, and at Stanford University and University College London. Many years of field research into ethnic conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, as well as the Caucasus, resulted in the book Why Men Go to War. His next long-term project, Big Houses – Big Dreams, is about people from the world’s poorest countries who became rich and put their money into dream homes. Dr. Haluzík works at the Centre for Theoretical Studies jointly run by Charles University and the Czech Academy of Sciences. He is the editor of, and contributor to, Město naruby (The City Inside Out) – about vague terrain, inner peripheries and in-between spaces. |

%20Petr%20Pokorný.jpg)

%20Petr%20Pokorný.jpg)

%20Petr%20Pokorný.jpg)

%20Petr%20Pokorný.jpg)

%20Petr%20Pokorný.JPG)

%20Petr%20Pokorný.jpg)