Petr Plecháč, completing a Ph.D. at Charles University, made world headlines with his analysis of Shakespeare’s Henry VIII. It was long accepted that the play was co-authored by playwright John Fletcher, but Plecháč’s study – using machine learning – analysed word frequency patterns and rhythms to provide further evidence that the play was a collaborative effort. Henry VIII was not written by Shakespeare alone.

Determining the differences required a granular approach by the academic, who explained the various aspects of the project, including why Shakespeare was so suitable for such an investigation:

“My Ph.D. thesis explored the possibility of using versification features – such as rhythm or rhyme – to help determine authorship or authorship recognition. I chose Shakespeare’s Henry VIII for a number of reasons. For one, there was a lot of training data upon which to build, namely all of the plays by Shakespeare, John Fletcher and Philip Massinger (also posited in the past as a possible co-author), and many lines written in iambic pentameter.

“Second, a strong hypothesis already existed that Henry VIII was a collaborative work. It was long understood that this play was not solely by Shakespeare, so that made it a good choice. Finally, there is the fact that all of Shakespeare’s work has been digitised. Those were all factors that led me to focus on this play.”

In practice it meant separately inputting not only the play but extensive work by both playwrights (as well as Massinger, seen as a less likely candidate for co-authorship) into a machine learning system, and familiarising it with their individual approaches.

“The general principle was that I collected different works of the playwrights in around the same period that Henry VIII was written, and I trained the algorithm to recognise their styles. After this information was input, the trained model was then applied to Henry VIII. The first thing you do when you train the model is test how it performs on known data and you perform cross-validation. That means you leave out one play by Shakespeare and train the rest and then run it on the one that was taken out. And you do the same with Fletcher. And the model reacts and labels the data in cases where you already know the correct answer. This way, you can estimate the accuracy of the model and how reliable it is. In my case it was very reliable: in 99 percent of cases it was able to determine authorship correctly.

“When we talk about versification, it means focusing on stress patterns – bit strings that represent stressed and unstressed syllables. It’s much easier today because these days we have very reliable software libraries that offer all kinds of machine learning and the machine learning part is easier to implement through a few lines of code. What is more difficult, is extracting these bit strings, these stress patterns from a text, but I was lucky that I was able to use software that had been developed at Stanford University by Ryan Heuser that had even been tested on Shakespeare’s work. There was evidence it would perform pretty well.”

Those patterns are far too numerous and interconnected to ever be successfully mapped by humans - effectively an impossible and largely fruitless task. That is why machine learning proved so useful, especially since changes could be made to existing software that Plecháč used.

“It is possible to tweak existing software a little bit or to tune its parameters, this is annotation versus versification level. First, you need to label the data, you need to tokenise it, to split the text into words. Also you need to mark the stresses, which syllable carries the stress and which does not, and then comes the analysis – training the machine to recognise the work and that is where my coding began. Of course, I didn’t code it from scratch and a mistake in some of the articles that came out about my work was that I used neural networks – I did not. It was a very popular technique in authorship recognition called support vector machine. And that is not my invention. I used general machine learning software libraries that were designed for this purpose.”

In the end, his findings further cemented that Henry VIII was a collaborative work, as was first posited by James Spedding in 1850.

“There are tiny, tiny differences when it comes to the frequency of words: someone uses the definite article far more often, someone will use by, another nearby, and language is unconscious. Stylometry focuses on these tiny differences that are very hard for a human to detect. If you or I read Henry VIII, we can focus on different aspects, who uses ye more often than you, or feminine endings in lines, but this would occupy all of our time. As humans we cannot focus on hundreds of different details simultaneously. In the end, each scene, in each play, is represented by one thousand variables; each scene is represented as a vector in 1000 dimensional vector space.”

Plecháč says he never expected his work to cause the sensation it did and says that is only good news for the field of Versification Studies, which have a tradition in Slavic countries like the Czech Republic but are virtually unknown anywhere else.

“Not that long ago, few people in English-speaking countries had heard of versification studies before so it is the first time readers heard about something like that. I never expected the article to cause such a sensation. I had gone to San Francisco for a conference and then learned from a friend that a major Hungarian paper had reported on my work, which was followed by CNN and then article after article around the globe. That kind of thing doesn’t happen really very often to people specialising in versification. I received emails from some really big names, asking me to collaborate on future projects. So that has been very positive and the interest overall has been very important for the field.”

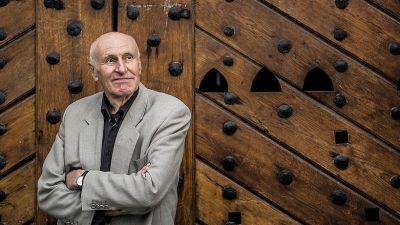

| Petr Plecháč, Ph.D. | |

|

Petr Plecháč, Ph.D., completed his first doctorate in theory of literature at Palacký University in Olomouc and his second, in mathematical linguistics, at the Faculty of Arts at Charles University. He made world headlines with his research of authorship in Shakespeare’s Henry VIII. Plecháč works at the Institute of Czech Literature at the Czech Academy of Sciences and at the University of Basel. |

| Shakespeare’s Henry VIII – How much do we really know? |

|

Petr Plecháč’s research has gone a long way in determining co-authorship but this “primer”, by translator and Shakespeare expert Martin Hilský, fills in some of the blanks about the play itself. Hilský discusses a number of topics including the contribution of machine learning. It’s important to note that there are details where we are still very much in the dark and which may never be known.

Professor Hilský:

A valuable contribution

We suspected for a long time and today it is understood that Shakespeare co-wrote Henry VIII. But that wasn’t always the case. Many scholars still had serious doubts even after Spedding posited John Fletcher as the co-author in 1850. For a long time, the idea that Shakespeare had co-written a play was simply unacceptable for some distinguished scholars, whereas today we know it is true. The reason Petr Plecháč’s work is so valuable is because it confirms – by a different means and different methodology – the co-author’s participation. I am not a mathematical linguist, but the methodology was captivating, which is why it was picked up by everyone from CNN to MIT Technology Review.

The contours of Shakespeare and Fletcher’s cooperation

We know very little about the actual collaborative process, almost nothing about the ways this co-authorship was organised. Did Shakespeare ask Fletcher to help him or was it the other way around? John Fletcher was a young playwright who was much more in fashion by then – we are talking about Jacobean England in the late period of Shakespeare’s career. Who asked whom is an important question because it shows trust in the other person’s abilities and shows where the power lay in the relationship. But we don’t know. Who had the dominant voice? Who decided the plot?

Untruths

The original title was not Henry VIII but All is True and I find that very funny because in this play there is a lot that isn’t true. Henry himself is not depicted at all as the architect of the English Reformation. Early on, Henry was a very charismatic king who later became a despot and tyrant who had two of his wives beheaded. But none of that is mentioned. You can say the play is only about the early part of Henry’s reign from around 1520–1533 when Elizabeth was born (who became the legendary Elizabeth I). Was it a conscious decision by Shakespeare or Fletcher to ignore what came later? Did they debate the issue?

Fletcher’s style

It is certain that his style was different but I don’t know that you can compare whether one was “better”, they were simply radically different and Fletcher’s approach by then was more modern and more fashionable. One example: Shakespeare never wrote so-called romances – Cymbeline, The Winter’s Tale, and The Tempest – until later, after 1608. That is because his company, the King’s Men, had not only The Globe Theatre at their disposal later on but also the Blackfriars, a private theatre that enabled scenic effects needed in romances that would not have been possible at The Globe. The romances were very much dependent on visual, baroque effects and Fletcher was simply much better at this. He was younger, on his way up, so to speak, whereas Shakespeare, while not in decline, was nearing the end of his career.

Co-authorship was widespread – but only a handful of Shakespeare’s plays were co-written

One thing that is important to point out is that in Shakespeare’s day co-authorship was common. What is remarkable and hugely surprising by contrast is that so few of Shakespeare’s plays were written in cooperation with anyone else. We do find co-authorship at the beginning of his career and at the end – but not in the middle. I have no explanation for this, except perhaps that Shakespeare was an actor as well, but roughly before 1605 he stopped acting and therefore perhaps he had more time for authorial cooperation and could spend more time debating with someone else.

The early plays are co-authored, obviously: Titus Andronicus, the first tragedy, was co-authored by George Peele (Shakespeare’s older contemporary) according to contextual scholars [Editor’s note: the matter is still debated and not a universally held view]. We know that Shakespeare alone wrote all of the major plays. After 1605, comes Macbeth, which was co-authored by Thomas Middleton, especially the witch scenes, then comes Timon of Athens that is a very interesting cooperation with Middleton, who was a completely different type of playwright, much more satirical. Then you have Henry VIII and The Two Noble Kinsmen, the last collaboration with John Fletcher. That’s it. The majority of Shakespeare was written by Shakespeare alone. |