Can you imagine analysing a buried vessel once used to share 150 litres of beer? Or investigating an ancient burial site for elites from the Hallstatt culture in the Moravian Karst? Archaeologist and Charles University doctoral student Zuzana Golec Mírová has done that and more - making a number of significant finds on her own as well as in broader teams. To hear her talk about archaeology is nothing less than thrilling.

When did you first get interested in the field?

I first became interested in archaeology when I was just a little kid. I was only around five when I saw a documentary about the Holy Grail and I found it fascinating. The impression stayed with me. It made me want to read everything I could about it and later to even learn French so I could be like Jean-Francois Champollion – the founder of modern Egyptology! I very much wanted to be an archaeologist but it was only much later, of course, after my last high school exam, that I was accepted at the Dept. of Archaeology at Palacký University in Olomouc. The feeling of getting accepted, not long after my final, was amazing.

What period in human history or prehistory caught your interest?

I was always interested in periods that presented many unanswered questions or mysteries. Many of my fellow students were interested in the Palaeolithic but I was drawn to the Bronze and Iron Age and specifically the Hallstatt period dating back to around 800 BC up to around 450 BC. I had fallen in love with precisely made artefacts from that time: beautiful jewellery, gold and bronze as well as glass and amber objects, or items like horse-drawn wagons. At first – to my shame – I didn’t know anything about the Hallstatt period, but I settled on studying this era because I was attracted to the artefacts they left behind.

Who were the Hallstatt people?

In the Czech milieu, it is a matter of debate and they are often referred to simply as Iron Age people. However, they are also often termed the Early Celts, which I think is fine for a popular understanding of who they were. Even if we have no idea what they called themselves.

You joked in one interview that you chose the Hallstatt period over earlier times because in the Palaeolithic they ate horses while here they used them to pull wagons and then began to even ride them. Of course, you also ride yourself.

That’s true! (laughs) I began riding at the age of 10 although not consistently: there were many interruptions or pauses. However, I still ride now. Being on horseback allows you to survey beautiful nature around you and riding is a feeling of freedom.

In the Hallstatt period, draft horses were common but they were only about 130 centimetres tall, almost like ponies. Larger horses were brought to this part of Europe at around that time and some of these were up to 147 centimetres. Not surprisingly, these were coveted by the elite. The horses – and being able to ride them – became an important status symbol.

The Hallstatt people were also in other parts of Europe, today’s Germany and Austria, and in Moravia. You conducted a lot of research here which we will get to shortly. But before that, you were also involved in a remarkable study of a large vessel found in the region of Pardubice, east of Prague. From the same period.

That’s a nice story. In 2017, the vessel was accidentally found by a gentleman named Pavel Rybka during a walk and he contacted archaeologists to excavate the item, also contacting the East Bohemia Museum in Pardubice. The find brought together archaeologists from Bohemia and Moravia, who organised the excavation including the soil inside. We created a broader team for soil analysis. People naturally think the vessel is the most valuable thing but, in this case, the same was true of the soil, from which we hoped to gather new information.

To get to the soil, you had to – at the same time – conserve the item. Was that tough to do?

The vessel is large: about 80 centimetres in height with a volume of 150 litres. It was difficult and expensive to conserve and not a quick process, because if you were to just shovel the dirt out, it would collapse.

What was the vessel used for?

What something was used for is always a tough question to answer but we already had a few clues: the item was found away from the usual settlement area. The volume suggested a beverage for a large number of people, which made it likely to have been used in a ritual. The answer was in the soil. Because we did broad content analysis, with botanists, chemists, palynologists and others who studied the starch, we determined that the soil contained traces of not just herbs but what was the oldest herbal-millet beer discovered in this part of the world. As for the item, the decoration on the vessel was also unusual, depicting mythological motifs: waterfowl pulling a solar barge, or the Sun, in the sky.

What did the analysis reveal about the taste?

It was clear it must have been very sour and bitter – so a type of beer immediately came to mind. But at this point it still hadn’t been confirmed. A lot of research went into comparing finds in the Balkans and Africa but it was analysis of the starch from colleagues in České Budějovice that confirmed the drink had been boiled and fermented. That was the last proof it was this herbal-millet beer. That confirmation led to our results being published in the prestigious British journal Archaeometry. It was a success, we had some citations and at least one team, in Siberia, built on our methodology and approach.

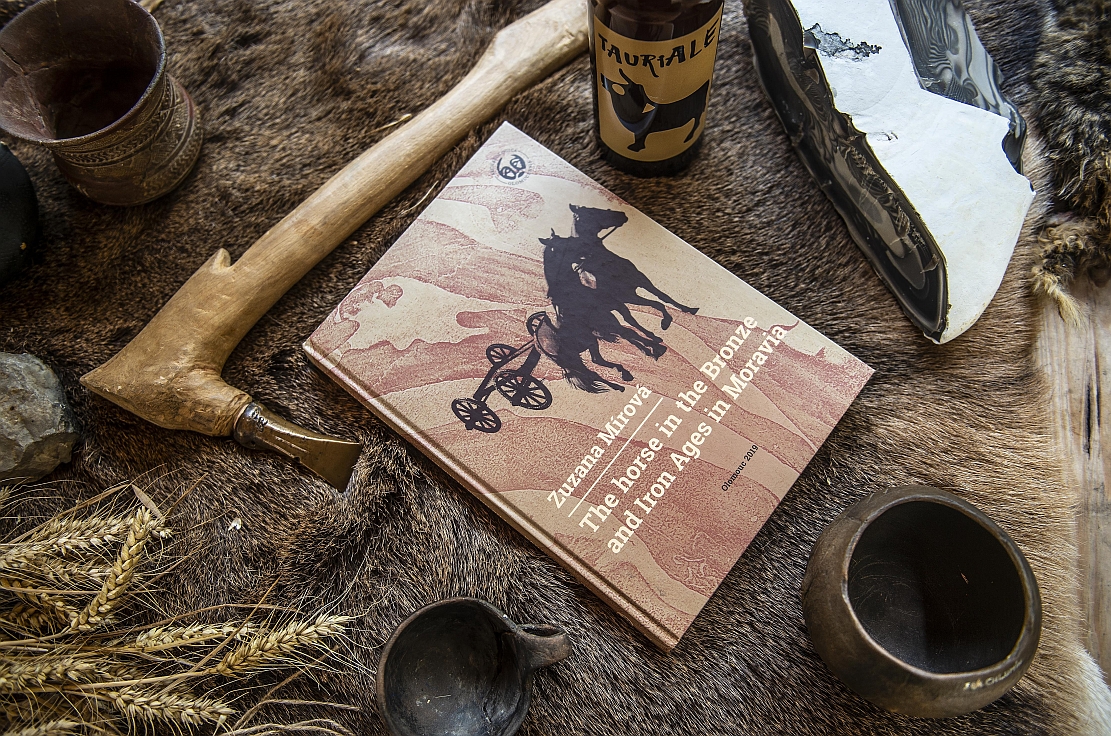

Since this success, you applied the methods you used and developed on similar samples you found in a famous cave called Byčí skála (Bull Rock or Bull Rock Cave) in the Moravian Karst, which was an area used by those early Celts in the Hallstatt period. You were able to put together a second beer recipe, one that you had brewed and bottled in limited quantities for promotional purposes. That cave at Byčí Skála was hugely important in Hallstatt culture.

In this case, we didn’t have a single vessel but we decided to recreate the recipe based on millet and other traces of herbs found in the cave itself. Thanks to the Department of Analytical Chemistry of Palacký University, the Institute of Botany of the Czech Academy of Sciences and the Laboratory of Archaeobotany and Palaeoecology of the University of South Bohemia, we were able to determine the recipe. We asked our friends Martina Duchoslavová and Richard Antl, from a local brewery called Lesia, if they would create the beer for us for special occasions and promotion, like museum days, and they agreed. The beer is called Tauriale with Taurus, of course, meaning bull. I brought a bottle in for you to try and you can tell me what you think.

Ok, I’m game.

Here you go… but be careful it’s very…

Sour! It’s very sour! Wow!

It is. And I forgot to say they also included honey in the recipe.

I can’t taste any honey! Very unusual. Here’s what I’d say: even if I was a beer person it would take some getting used to. Still, it’s amazing to think they drank something like this in the Iron Age. What did your colleagues or other people say about it?

I think they like it.

If this beverage was a facilitator in shared ritual, what did these famous cave systems in the Moravian Karst represent? Were they important in ritual as well?

In the Neolithic period they would have used the entrance part for shelter and did cave painting much further inside, for example at the Kateřinská cave, the oldest in the Czech Republic. If we jump far ahead, to the Middle Ages, the caves were used by counterfeiters of money. And during the Hallstatt period they buried their deceased inside – the cave was used as a tomb for elites. It is one of the top Hallstatt sites in all of Europe and was used for around 120 years, so there were many generations of elites buried there along with their possessions including glass items and weapons and wagons. Some of them were wagon graves. It is a huge necropolis and burial ground, something that didn’t exist in the open landscape. It is of world importance, a very important site.

It is the also the place that remaining parts of once elite iron covered wagons were found in the past but their importance not understood. You connected the dots by researching in depositories. What you found suggested there were connections between different sites…

I realised that previously we knew of only one such wagon in all of Europe, found at the Hochdorf chieftain’s grave in Baden-Württemberg, Germany from the Hallstatt culture and in the depository I found we had evidence of a twin in Moravia 800 kilometres away! In fact, we had at least six more similar metal-covered – bronze and iron – wagons at one site. Now we know of 13 beautifully decorated metal covered wagons in Europe but six were found at one place in the Moravian Karst. That is very unusual. Surviving parts had all been taken to depositories many years before but nobody paid the remains of these wagons much attention. Rusted iron looks much worse than bronze lying in a corner and nobody connected the dots before I looked into it. That is what I found.

The archaeologist and colleagues regularly organise popularisation events to raise awareness of finds and research in their field.

When you realised there were these connections it must have been like solving one of the best mysteries, ever!

Exactly! I couldn’t believe I had uncovered what was basically Hochdorf wagon No. 2. But I have since discussed it with colleagues in Baden-Württemberg and other colleagues in Austria who confirmed as much!

It must be very rewarding, with finds like this, to know you are also popularising archaeology, whether with publications about ancient beer or elite iron covered wagons. I mean, how can audiences not be drawn in!

Popularisation is an important aspect of what we do. We need to enjoy informing the broader public about our work and what we receive funding for. That is very important.

| Hallstatt Period costume |

|

When Zuzana Golec Mírová posed for our cover, she wore a Hallstatt Period costume based on findings from Byčí skála cave. It is a costume that would have been worn by the elite, representing the greatest luxury in society at the time. Red was considered a luxurious colour, the tablets – the borders of the clothing – were inspired by the finds from the Hallstatt burial ground. Women in that time also wore a veil on their heads. The biggest speciality is a compound belt of Moravian type with a central disc with a sun motif. It consists of 22,000 subtle bronze rings woven into the fabric. For the photoshoot, Zuzana also wore bracelets and characteristic navicella-type fibulae. Her necklace is made of several hundred amber and glass beads. |

A lot of this sounds like very detailed, patient and fascinating work on so many levels. But you are not alone on your archaeological journey. Your husband, Martin Golec, is also a well-known archaeologist and academic. Sometimes couples in the same fields work closely together and sometimes they do not. What about you as a couple?

I love it! I love working together! Imagine you have something like home office and you make a discovery: you can immediately share it with another scientist. Sometimes it is difficult: we say, “Ok, now we will go for a nice walk and we won’t talk about science or archaeology,” and then for the next three hours we discuss… archaeology! New ideas and new projects. Sometimes it feels like you never leave work but it really helps to develop ideas more quickly. You always have something to talk about and you never have silent nights!

| Zuzana Golec Mírová |

| Zuzana Golec Mírová studied archaeology at Palacký University in Olomouc. She focuses mainly on the Bronze Age and the earlier Iron Age and is currently most engaged in research on social elites. She also deals with e.g. the horse in prehistoric times or the application of chemical methods in archaeology (e.g. analytics of the origin of amber). Since 2019 she has been pursuing PhD studies at the Institute for Archaeology, Faculty of Arts of Charles University in Prague. Her forthcoming dissertation is entitled "Centralization and decentralization processes of the 14th-4th century BC in Moravia". Zuzana Golec Mírová has lectured at Palacký University in Olomouc, Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen, Universität Wien, the University of Edinburgh and the University of Bologna. At Charles University she teaches a lecture course called the Early Iron Age in the Central European context on the example of Moravia and Hallstatt and La Tène Periods. |