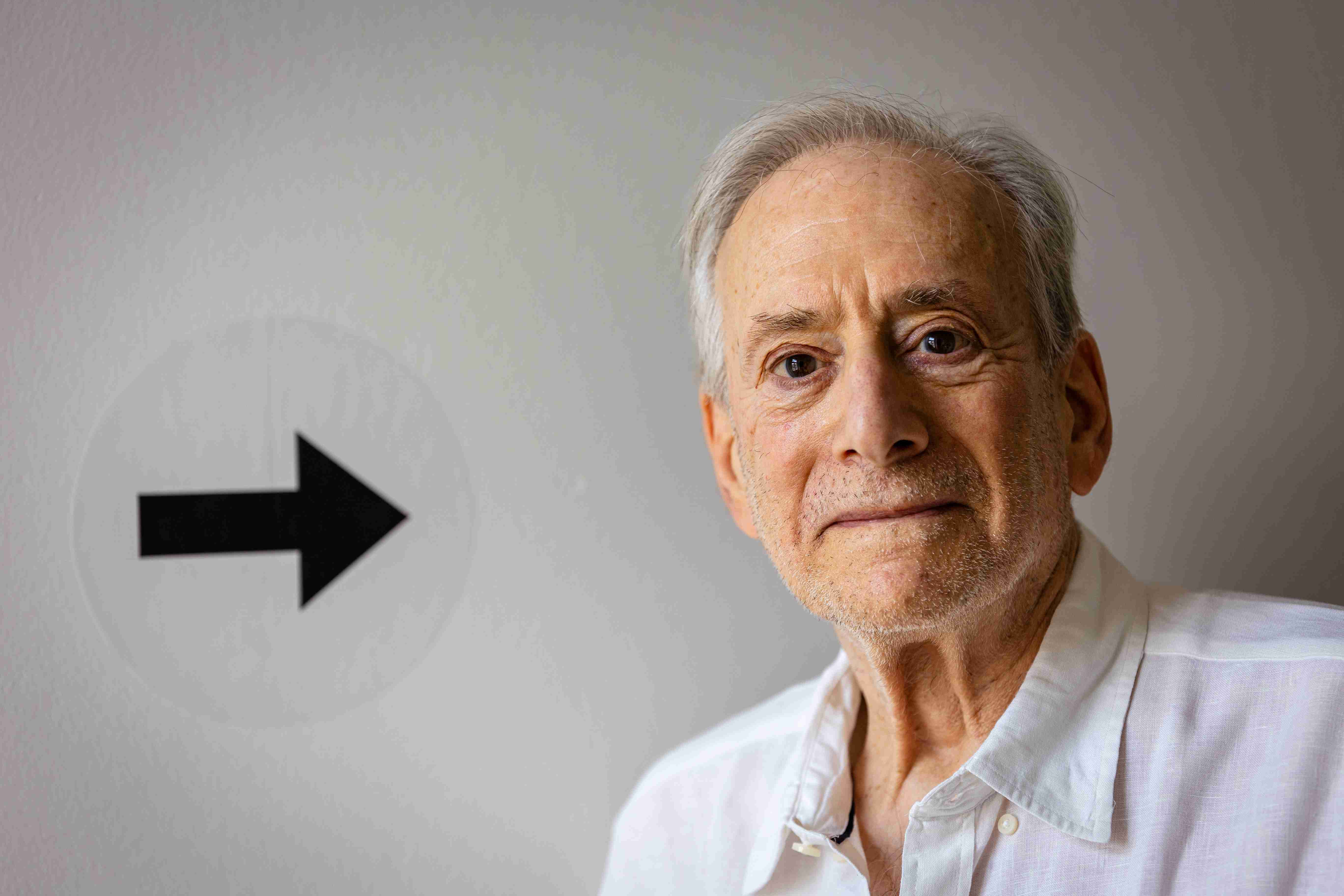

One of the most influential American archaeologists, Professor Harvey Weiss of Yale University is well known for his pioneering work in environmental archaeology and for advancing the theory that mega-droughts played a central role in the collapse of ancient civilizations in both Mesopotamia and Egypt. His research, including influential articles published in Science magazine (1993, 2001), has reshaped how we think about the relationship between climate and societal resilience. “I’ve always been interested in how human societies were affected by their environments and by natural events,” Weiss told the Charles University media and Forum magazine.

One of the most influential American archaeologists, Professor Harvey Weiss of Yale University is well known for his pioneering work in environmental archaeology and for advancing the theory that mega-droughts played a central role in the collapse of ancient civilizations in both Mesopotamia and Egypt. His research, including influential articles published in Science magazine (1993, 2001), has reshaped how we think about the relationship between climate and societal resilience. “I’ve always been interested in how human societies were affected by their environments and by natural events,” Weiss told the Charles University media and Forum magazine.

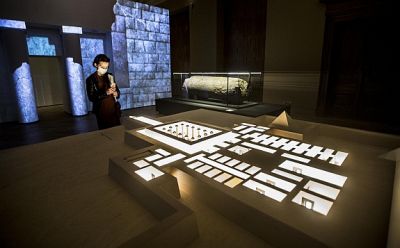

Harvey Weiss came to Prague in the beginning of July at the invitation of Professor Miroslav Bárta to participate in a major international Egyptology conference called Old Kingdom Collapse at 4.2 ka BP Reconsidered: New Perspectives and New Agendas from the Environmental and Social Sciences. This conference, held on 2nd and 3rd July at the Kampus Hybernská venue, was co-organized by Weiss and the Czech Institute of Egyptology at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University.

The conference featured numerous renowned speakers including Charles University scientists, archaeobotanist Claire Malleson (American University in Beirut, Lebanon), egyptologists Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano and Carmen Romero-Fernández (Universidad de Jaén, Spain), Johannes Jüngling (Sächsische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Germany), Julian Posch (Universität Innsbruck, Austria), Richard Bussmann (Universität zu Köln, Germany), Alexandre Loktionov (University of Cambridge, UK), Laure Pantalacci (Université Lumière-Lyon 2, France), Karin Sowada (Macquarie University, Australia), Amin A. O. Gholami and Carmine Guerriero (Università di Bologna, Italy), as well as Aaron Gidding with Thomas Evan Levy (University of California San Diego, USA) who was awarded Charles University’s doctorate honoris causa in the historical Karolinum (2018).

We met with professor Harvey Weiss of Yale University in the setting of Kampus Hybernská on a very hot, sweltering afternoon for a conversation that ranged from ancient climate disasters to the current state of science and politics in America.

Thank you for your time, Professor Weiss. You’ve come to Prague – have you ever been here before? Have you visited the Czech Republic before?

No, this is my first time. I love Prague. I love Charles University. I love Mirek (laughs).

Have you collaborated with Miroslav Bárta before?

No, this is our first opportunity.

So what led to your co-organization of this conference in Prague?

Well, Mirek is one of the world’s leading authorities on the Old Kingdom of Egypt. He has done extensive and important research on the collapse of the Old Kingdom and has published widely on the topic. When you think about the collapse of the Old Kingdom, you think of Mirek – and Prague. So it was natural to be involved in a conference that he organized.

I’ve always been interested in how human societies were affected by their environments and by natural events.

Over the past two decades, we’ve learned that past climates were not uniform or stable – they were punctuated by high-magnitude events, like mega-droughts. These events had a dramatic impact, even on highly developed, complex societies in regions like Mesopotamia and Egypt. If you want to understand that process, you come to Prague.

Could you share some highlights from the conference?

Certainly. There have been numerous fascinating reports on Egyptian archaeology presented by my Czech colleagues from the Charles University in Prague, as well as by scholars from around the world – from Australia, USA, Germany, Italy, France, Spain, and more. It’s been an intellectually rich experience.

Much of this work is coordinated or inspired by Mirek Bárta’s leadership and vision. His influence on the field is significant.

It’s been unusually hot in Prague during the conference. Is this climate-related?

Probably. Climate change may be playing a role. Yesterday, it was extremely hot – I gave a lecture in that heat, which was quite a challenge.

This seems to be a very interdisciplinary conference, isn’t it?

Yes, very much so. We’ve had presentations on archaeology, climate science, environmental history, and how ancient societies responded to changing environmental conditions. It’s been fascinating to engage with colleagues from various disciplines whom I might not otherwise have met.

“The Old Kingdom of Egypt experienced the same kind of mega-drought as Mesopotamia,” says archaeologist Harvey Weiss of Yale University.

And you specialize in environmental archaeology?

Exactly. I work primarily in Mesopotamia – Syria and Iraq.

I read that you launched the Tell Leilan Project in 1978. What was its focus?

Tell Leilan is a major ancient city in northern Syria that had never been fully explored. I went there to study the ancient civilization of the region – to understand how they produced food, how their agricultural systems worked, and how society changed over time. It was a remarkable experience, particularly in those years before the war and the disaster that followed.

Have you been back to Syria in recent years?

Have you been back to Syria in recent years?

No, not recently. The situation has changed dramatically.

You’ve certainly traveled widely – to Syria, Iraq, Iran… What have been your most meaningful experiences in Near East?

The people. The people of those countries are extraordinarily gracious, kind, and generous. Meeting and working with them has been the most rewarding part of my career.

What made you shift your focus from Mesopotamia to the Old Kingdom in Egypt?

The Old Kingdom of Egypt experienced the same kind of mega-drought as Mesopotamia. After researching the Mesopotamian collapse, I wanted to understand what happened in Egypt during the same period. That’s how I met Mirek and how this conference came about.

Your famous Science article was titled What Drives Societal Collapse, right?

Yes, exactly. That article argued that significant climate events occurred in the past and that ancient societies were vulnerable to them. That was the central message of the article.

Were mega-droughts the only cause of collapse, or are there others? Professor Bárta, for instance, talks about seven laws of collapse – including bureaucracy and so on.

That’s Mirek’s framework. My research focuses primarily on mega-droughts because we have strong, empirical data for those events.

That’s Mirek’s framework. My research focuses primarily on mega-droughts because we have strong, empirical data for those events.

Do you see any parallels between ancient societal collapse and challenges we face today?

There is a fundamental difference. In the past, climate change events were entirely natural. Today, they are almost entirely anthropogenic, caused by human activity. That’s the key difference. And that’s the lesson for us.

What is it like doing science in the USA today, under the administration of President Donald Trump or secretaries such as Robert F. Kennedy Jr.?

The scientific community is being actively undermined. Science is being destroyed.

And it’s entirely unnecessary. It’s a political agenda that is deeply disturbing.

| prof. Harvey Weiss, PhD |

| Professor of Near Eastern Archaeology and Environmental Studies at Yale University, where he has taught for several decades. He is best known for his leadership of the Yale Tell Leilan Project in northeastern Syria, which he launched in 1978. His fieldwork at this major ancient urban center has yielded groundbreaking insights into the origins, development, and collapse of early Mesopotamian civilizations. Weiss’s research focuses on the relationship between environmental change and societal transformation in antiquity. He was among the first archaeologists to argue, based on hard data, that abrupt climate events – particularly multi-century mega-droughts – were key drivers in the collapse of complex societies. His influential articles in journals such as Science (1993, 2001) have had a lasting impact on both archaeological theory and climate history, sparking interdisciplinary collaborations between archaeologists, climate scientists, and historians. He continues to advocate for integrated approaches to understanding past societal resilience and vulnerability – lessons that are relevant to the global climate challenges we face today. |